By His Highness the Aga Khan, Sir Sultan Mahomed Shah

(1877 – 1957)

A portrait of Sir Sultan Mahomed Shah, His Highness the Aga Khan III, dated 1911, Copyright: National Portrait Gallery.

There had been sinister rumors that an epidemic of bubonic plague was sedulously and remorselessly spreading westward across Asia. There had been a bad outbreak in Hong Kong; sporadically it appeared in towns and cities farther and farther west.

When in the late summer of 1897 it hit Bombay there was a natural and general tendency to discredit its seriousness; but within a brief time we were all compelled to face the fact that it was indeed an epidemic of disastrous proportions. Understanding of the ecology of plague was still extremely incomplete in the nineties. The medical authorities in Bombay were overwhelmed by the magnitude, and (as it seemed) the complexity, of the catastrophe that had descended on the city. Their reactions were cautious and conservative. Cure they had none, and the only preventative that they could offer was along lines of timid general hygiene, vaguely admirable but unsuited to the precise problem with which they had to deal.

A plague house being whitewashed by men standing on scaffolding in Bombay. Photograph, 1896. Photo Credit: Credit: Wellcome Library, London. Wellcome Images. Copyright.

Open up, they said; let fresh air and light into the little huts, the hovels and the shanties in

which hundreds of thousands of the industrial and agricultural proletariat in Bombay Presidency lived; and when you have let in fresh air, sprinkle as much strong and strong smelling disinfectant as you can. These precautions were not only ineffective; they ran directly counter to deep-rooted habits in the Indian masses. Had they obviously worked, they might have been forgiven, but as they obviously did not, and the death roll mounted day by day, it was inevitable that there was a growing feeling of resentment.

It was a grim period. The plague had its ugly, traditional effect on public morals. Respect for law and order slipped ominously. There were outbreaks of looting and violence.

….article continues following excerpts I and II related to the vaccine’s development

________________________________________________________________________________

HAFFKINE, THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE VACCINES, AND THE FIRST INOCULATION

– I –

Waldemar Mordecai Haffkine. Photo Credit: Wellcome Library, London. Wellcome Images. Copyright.

Waldemar Mordecai Haffkine developed an anticholera vaccine at the Pasteur Institute, Paris, in 1892. From the results of field trials in India from 1893 to 1896, he has been credited as having carried out the first effective prophylactic vaccination for a bacterial disease in man.

In June 1894 bubonic plague reached Hong Kong, having spread from the endemic region of South China…..In late September 1896, the plague reached Bombay…. the Government of India, impressed by the anticholera vaccine, requested Haffkine to go to Bombay to devise, if possible, a similar vaccine to combat the dreadful disease. On 8 October 1896 Haffkine entered the Indian Civil Service.

Major William Burney Bannerman, Indian Medical Service (IMS) (1859–1924), described the subsequent events:

[That day Haffkine] began work in a room in the Petit Laboratory of Grant Medical College. His laboratory consisted of one room and a corridor, and his staff of one native clerk and three peons or messengers. It was here that Mr Haffkine made the discovery of the stalactite growth assumed by the plague bacillus when grown in nutrient broth, which will ever be connected with his name as a reliable and easy means of diagnosing the organism. In December 1896 Mr Haffkine was successful in protecting rabbits against an inoculation of virulent plague microbes, by treating them previously with a subcutaneous injection of a culture in broth of these organisms sterilised by heat. The rabbits treated in this way became immune to plague. On the 10th January 1897 Mr Haffkine caused himself to be inoculated with 10c.c. of a similar preparation, thus proving in his own person the harmlessness of the fluid.

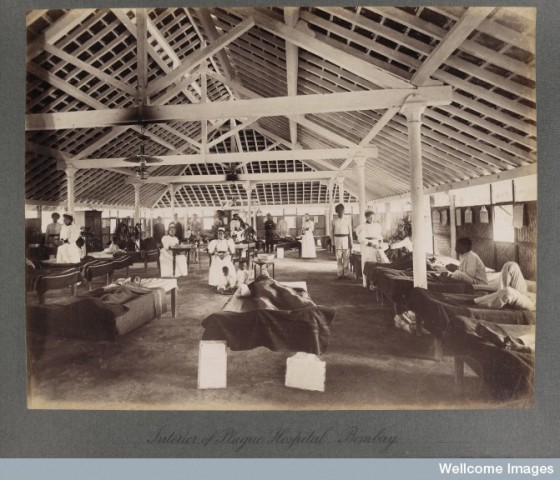

Interior of a temporary hospital for plague victims, Bombay plague epidemic, 1896-1897 Photo Credit: Wellcome Library, London. Wellcome Images. Copyright.

Haffkine chose to be inoculated with a much higher dose of the broth and sediment than the 3 cl3 to be given to the public. Side-effects were restricted to pain at the seat of injection and an attack of fever that produced malaise for about two days.

Experience gained from testing the anticholera vaccine was now used to try and evaluate the effectiveness of the antiplague vaccine…..Haffkine arranged to inoculate 154 prisoners who volunteered. Three of the inoculated men died that day but in the following six days there were no deaths. Of the 191 untreated men, three died on the inoculation day and six in the following six days. When an apparent protection conferred by the vaccine became known, great demand for the prophylactic commenced. Over 11,000 individuals in the infected areas were inoculated in the next three months. Twice that year the laboratory needed to move to bungalows owned by the Bombay Government as production of the vaccine expanded.

In 1898 the laboratory moved to Khushru lodge owned by Sir Sultan Shah, Aga Khan III, KCIE (1877–1957), head of the Khoja Mussulman community. This bungalow was fitted up at the Aga Khan’s expense for Haffkine’s use and about half the Khoja Mussulman community of Bombay (10,000–12,000 persons) received prophylactic inoculations under the auspices of His Highness the Aga Khan….

(excerpts include selections from “Waldemar Mordecai Haffkine, CIE (1860–1930): prophylactic vaccination against cholera and bubonic plague in British India”, By Barbara J. Hawgood. For her complete article, please click Jameslindlibrary.org).

_______________

– II –

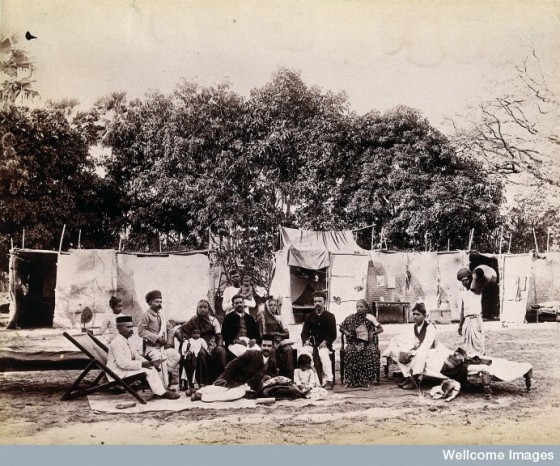

A group of people who worked as volunteers during the plague epidemic in Bombay. Photograph attributed to Captain C. Moss, 1897.

On the 10th of January 1897 Mr Haflfkine caused himself to be inoculated with 10 c.c. of a similar preparation, thus proving in his own person the harmlessness of the fluid. Shortly after this, various medical Men and prominent citizens of Bombay were publicly inoculated, to encourage others to submit to operation ; but it was not till the publication of the result of inoculating half the prisoners in the House of Correction at Byculla, in Bombay, that the measure became popular. Increased popularity involved more wholesale manufacture of the prophylactic, and this necessitated removal to ‘The Cliff’ bungalow, Malabar Hill, which was placed at Mr Haffkine’s disposal by the municipality of Bombay. The staff had now been increased to two military assistant surgeons, two clerks, three peons and four hamals or house-cleaners.

An affluent family forced to leave their home due to plague. Photo Credit: Wellcome Library, London. Wellcome Images. Copyright.

The Cliff was occupied from April to November 1897, when a second move had to be made to another bungalow in Nepean Sea Road. At this time H.H. Sir Sultan Shah, Aga Khan, E.C.I.E., the head of the Khoja Mussulman community, who had been early convinced of the efficacy of inoculation, fitted up at his own expense Khushru Lodge, one of his bungalows in Mazagon, for Mr Haffkine’s use…. — From the Proceedings of the Royal Society of Edinburgh Vol XXIV, November 1901 to July 1903. Please click Proceedings Royal Edinburgh Society

________________________________________________________________________________

….excerpt by His Highness the Aga Khan, continued

Drunkenness and immorality increased; and there was a great deal of bitter feeling against the Government for the haphazard and inefficient way in which it was tackling the crisis. The climax was reached with the assassination (on his way home from a Government House function) of one of the senior British officials responsible for such preventative measures as had been undertaken.

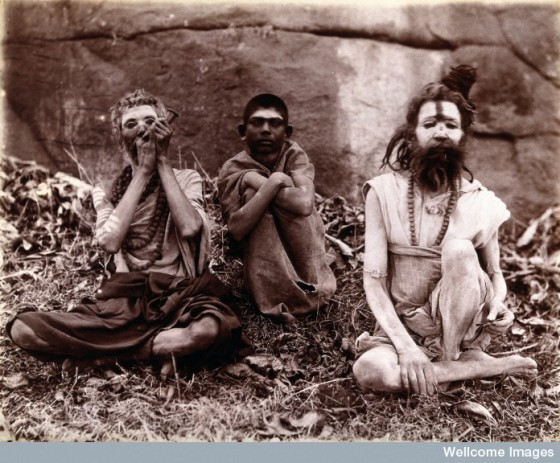

Two men and a boy sitting cross-legged on the ground surrounded by leaves; their faces are painted white and one of them appears to be smoking a pipe: Bombay at the time of the 1896/97 plague. Photo Credit: Wellcome Library, London. Wellcome Images. Copyright.

Now it happened that the Government of Bombay had at its disposal a brilliant scientist and research worker, Professor Haffkinez, a Russian Jew, who had come to work on problems connected with cholera; he had induced the authorities to tackle cholera by mass inoculation and had had in this sphere considerable success. He was a determined and energetic man. He was convinced that inoculation offered a method of combating bubonic plague. He pressed his views on official quarters in Bombay — without a great deal of success. Controversy seethed around him, but he had little chance to put his views into practice. Meanwhile people were dying like flies — among them many of my own followers.

A group of officials making a visit to a house in Bombay, suspected of holding people with plague. Photo Credit: Wellcome Library, London. Wellcome Images. Copyright.

I knew that something must be done, and I knew that I must take the initiative. I was not, as I have already recounted, entirely without scientific knowledge; I knew something of Pasteur’s work in France. I was convinced that the Surgeon General’s Department was working along the wrong lines. I by-passed it and addressed myself directly to Professor Haffkine. He and I formed an immediate alliance and a friendship that was not restricted solely to the grim business that confronted us. This, by now, was urgent enough. I could at least and at once give him facilities for his research and laboratory work. I put freely at his disposal one of my biggest houses, a vast, rambling palace not far from Aga Hall (it is now a part of St. Mary’s College, Mazagaon); here he established himself, and here he remained about two years until the Government of India, convinced of the success of his methods, took over the whole research project and put it on a proper, adequate and official footing.

Meanwhile I had to act swiftly and drastically. The impact of the plague among my own people was alarming. It was in my power to set an example. I had myself publicly inoculated, and I took care to see that the news of what I had done was spread as far as possible and as quickly as possible.

My followers could see for themselves that I, their Imam, had in full view of many witnesses submitted myself to this mysterious and dreaded process; hence there was no danger in following my example. The immunity, of which my continued health and my activities were obvious evidence, impressed itself on their consciousness and conquered their fear.

I was twenty years old. I ranged myself (with Haffkine, of course) against orthodox medical opinion of the time — among Europeans no less than among Asiatics. And if the doctors were opposed to the idea of inoculation, what of the views of ordinary people, in my own household and entourage, in the public at large? Ordinary people were extremely frightened.

Looking back across more than half a century, may I not be justified in feeling that the young man that I was showed a certain amount of courage and resolution?

Bombay Municipal carts bringing in the rats. Photo Credit: Wellcome Library, London. Wellcome Images. Copyright.

At any rate it worked. Among my own followers the news circulated swiftly, as I had intended it to do, that their Imam had been inoculated and that they were to follow my example. Deliberately I put my leadership to the test. It survived and vindicated itself in a

new and perhaps dramatic fashion. My followers allowed themselves to be inoculated, not in a few isolated instances, but as a group. Within a short time statistics were firmly on my side; the death rate from plague was demonstrably far, far lower among Ismailis than in any other section of the community; the number of new cases, caused by contamination, was sharply reduced; and finally the incidence of recovery was far higher.

A man’s first battle in life is always important. Mine had taught me much, about myself and about other people. I had fought official apathy and conservatism, fear and ignorance — my past foretold my future, for they were foes that were to confront me again and again

throughout my life.

By the time the crisis was passed I may have seemed solemn beyond my years, but I possessed an inner self-confidence and strength that temporary and transient twists of fortune henceforth could not easily shake.

Date posted: Saturday, June 22, 2013.

Date updated: Sunday, April 7, 2020 (typos).

_________________

The above piece is adapted from The Memoirs of Aga Khan by His Highness the Aga Khan, 1954.

Photo Credits: The Wellcome Library London. The Wellcome Trust, is a UK based charity funding institution for research to improve human and animal health by supporting the brightest minds in biomedical research and the medical humanities. In addition to funding biomedical research, it supports the public understanding of science. In the field of medical research, it is the world’s second largest private funder after Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. Please visit their website by clicking http://www.wellcome.ac.uk/.

For more readings on the 48th Ismaili Imam, please click His Highness the Aga Khan III.

______________

We welcome feedback/letters from our readers. Please use the LEAVE A REPLY box which appears below. Your feedback may be edited for length and brevity, and is subject to moderation. We are unable to acknowledge unpublished letters. Please visit the Simerg Home page for links to articles posted most recently. For links to articles posted on this Web site since its launch in March 2009, please click What’s New.

Very interesting. I have never heard about this episode. I will now try to read the Memoirs of The Aga Khan.