“I Wish I’d Been There”

By Alice C. Hunsberger

I wish I had been in Cairo, Egypt, in 1048, to witness the Sultan’s “Opening of the Canal” ceremony, the annual breaking of the earthen dike holding back the Nile, letting the pent up river gush through the main royal canal and then rush off into hundreds of smaller channels throughout the countryside, drenching the thirsty earth with life-giving, nutrient-rich, silt-laden flood water. And I wish my guide for the day had been the poet from eastern Persia, Nasir Khusraw, whose travel memoirs have left us some of the richest descriptions of that ceremony, “one of the biggest holidays of the year.”

My guide Nasir explains that the importance of the ceremony is linked to Egypt’s absolute dependence on the flooding. “When the sun enters Cancer,” he writes, the Nile starts its rise, and everyday the Egyptian officials take measurements. Less than eighteen cubits rise is a disaster, and the Sultan will not levy taxes on the peasants. More than eighteen brings rejoicing and happiness, and harvests sufficient to store for lean years. The normal pattern, Nasir recounts, is forty days of rising, then forty days of stable settling, and then another forty days decreasing. As the Nile retreats, leaving a new layer of natural fertilizer all over the land, the people quickly plant new crops, following the speed and course of the river’s path. Canals and dikes are built all over the country, with so many waterwheels “it would be difficult to count them.” The Sultan’s canal is a grand piece of engineering, linking Old Cairo, founded by the Arab conquerors in the 7th century around the army town of Fustat, with New Cairo (al-Qahira), founded by the Fatimid conquerors in the 10th century.

Speaking Arabic and Persian, Nasir and I would have heightened awareness that the word “opening” itself (fath) carries other layers of meaning, such as conquests and victories, but perhaps more importantly, is the name of a Surah in the Quran, whose opening verses relate victory as the sign of God’s pardon for the Prophet Muhammad’s sins. But today, we are going to watch the opening of the canal by the Fatimid Sultan, Imam Mustansir billah.

Actually, I wish that three days earlier I had accompanied Nasir to see the hoopla of preparations in the Sultan’s stables. To hear drummers and trumpeters making as much noise as they could to prepare thousands of horses for the enormous din of the parade. What a din it would be! But even with such preparation and even with riders to calm them, Nasir points out that over ten thousand horses each had a man hired to hold the reins and walk the horse.

When all riders and marchers are ready, Sultan Mustansir mounts his camel, with the plainest saddle and bridle, with no gold or silver ornamentation. I would see, as Nasir does, that the Sultan is a “well-built, clean-shaven youth with cropped hair,” and his pure white Arab-style shirt is tucked into a cummerbund of the costliest fabric, with a turban to match. No one rides next to the Sultan except the parasol-bearer, who, in contrast, wears extremely ornate dress with a bejeweled, gold turban, and carries the royal gem-studded parasol, a sign of royalty, like a crown. I would have liked to study the intricacies of the embroidery and marvel at the jewel-studded ornamentation. I would have liked to be able to add more description of the stately procession.

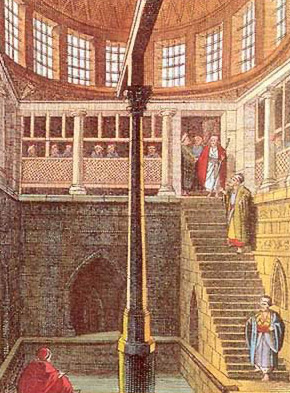

Because of its importance in determining the prosperity Egypt would experience during the following year, the Nilometer shown as a lithograph in the above illustration was a departure point of the greatest of Cairo's celebrations throughout the medieval period. This was the Fath al-Khalij, the "Riding Forth to Open the Canal." Image: TourEgypt.net

In my wish, Nasir Khusraw and I will march with the contingent of intellectuals, scholars, poets, literati, and experts on law and jurisprudence (all of us on fixed stipends, he is proud to say about Mustansir’s policies). But we are far behind the ranks of soldiers and political dignitaries and contingents of princes and their mothers from far and wide. When it is finally time to start, the trumpets, clarions and drums lead off and continue sounding down the whole route from Harem Gate to the head of the canal. Next come those horses by the hundreds, thousands it seems, each with a rider and walker. Nasir records ten thousand. These show-stoppers bedecked with gold saddles and bridles and jewel-studded reins, wear saddle-cloths of Byzantine brocade which shimmers iridescent with gold threads, with gold-embroidered inscriptions on the borders. From the golden pommels, hang weapons like spears, coats of mail, axes, swords, helmets and shields. The horses are followed by other mounts, hundreds of camels tall and lanky, and mules strong and focused, carrying curtained howdahs and other seats for ladies and children. I would have liked to see them all and hear the horses whinnying and blowing air, shaking their jeweled bridles and clopping their hooves on the stony road. I would have liked to see the Arabian horses’ eyes, with long lashes, their flanks twitching at the flies and sweat, their dramatic tails flicking around. I would have liked to see the shining fabrics (handiwork from the now lost island of Tinnis) glittering in the sun, reflecting off the gold and silver ornaments on humans, animals and everything else.

But that was just the beginning. Then would come thousands of soldiers, from every part of the Fatimid realm: they told us twenty-thousand horsemen from Kairouan, North Africa; fifteen thousand Batili horsemen from Morocco; twenty thousand Masmudi infantry; ten thousand “powerfully built” Turks and Persians (most born in Egypt); fifty thousand Bedouin from Arabia, with spears; thirty thousand slaves who had been purchased; foot soldiers from all over the world (Nasir counted ten thousand), as well as thirty thousand black Zanjis who fight with swords. Who can say for sure how many marched that day, filling the sky with dust and clamor? I wish I had been there, to tell you for sure.

And when we all arrived at the great tent set up at the head of the canal, and everyone assembled round, I would have liked to see the young Sultan Mustansir accept the spear and look around at the crowd, and we would nod, and he would throw the spear into the dike, and then, hundreds of workers would rush to dig away a hole in the dike. And when the water came rushing over filling the royal canal, I would have liked to hear the crowd raise up a roar, now grateful this year’s harvest was secure.

I wish I had been there, back in a time of respect for the river’s life-giving essence, not just its power. Back when the fertile flow flowed, and yes, was harnessed and used, but rejoiced in and welcomed, not stopped up and dammed to a trickle. This was my wish: To see how the great Nile River’s annual flooding, much hoped for, prayed for, and scientifically monitored, was gathered up into one day which brought peasant and Sultan together, with every rank in between, men and women, Egyptian and foreign. A day so full of life and significance that Nasir Khusraw apologizes, saying “If I were to give a full description of that Day of the Canal, my words would go on and on, far too long.”

© Simerg.com

___________

About the Writer: Alice C. Hunsberger has spent two decades studying the works of Nasir Khusraw. For her forthcoming book, Rhyme and Reason: The Philosophical Poetry of Nasir Khusraw (I.B. Tauris Press, IIS Publications), she has edited the proceedings from the 2005 international conference she organized (funded by Iran Heritage Foundation and Institute for Ismaili Studies), and added an extensive introduction. Rhyme and Reason will be the first extended study of Nasir Khusraw’s poetry both from the point of view of poetic art and philosophical meaning. Her first book, Nasir Khusraw: The Ruby of Badakhshan, has been translated into Persian, Tajik, Russian and Arabic. Dr. Hunsberger, a 1999-2001 Research Fellow at the IIS in London, teaches Islamic Studies at Hunter College in New York.

___________

1. For other published articles in this series, please click I Wish I’d Been There or visit the home page, www.simerg.com.

2. We welcome feedback/letters from our readers. Please use the LEAVE A REPLY box which appears at the bottom of this page, or email it to simerg@aol.com. Your feedback may be edited for length and brevity, and is subject to moderation. We are unable to acknowledge unpublished letters.

Hi there:

I am looking for all the works of Hakim Nasir Khoraw in English or Persian in pdf format as it is difficult to afford printed books. Any links to the pdf versions will be highly appreciated.

Mohammad Yameen.

Thanks Alice! All cases from Nasir’s ‘Safar-name” needs such smart reflections, for example, his meetings and discussions with scholars, politicians, ordinary people in different countries in Middle East, Yemen etc. What is important here is that Alice shows how it is possible to move text to work for modern time, refreshing the past and to be available for new interpretations…

Dear Alice

Since the conference of Nasir Khusraw in Tajikistan (September 2003), I became fascinated to read more and more about this great Philosopher. So your book “The Ruby of Badakhshan” and articles about Khusraw have attracted me more to him.

With all the best

Hatim Mahamid

In reading this beautiful text, it occurs as if the words are flowing in river and shining off the bright sunshine – as evoking and glimmering as the grand ceremony the author describes.

Many thanks ! It has brought alive so much beauty and quest from the brilliantly gifted author, Alice C. Hunsberger !

Dear Dr Hunsberger: As an educator I have used the technique of ‘guided imagery’ with success. I used the same technique to follow in your footsteps.I experienced not only the sights and sounds of this journey but also the smells. Thank you!

I have read “the Ruby” several times with increased understanding everytime. I wish I had been there when Nasr met his brother on returing from Haj. Thank you 1000*

Zul

Another chapter from our glorious history that comes alive with this “first hand” description of the event. Excellent reading!

Dear Dr. Hunsberger.

First of all thank you for contributing to Simerg.com’s excellent series of I Wish I’d Been There. It is nice to associate a picture with the author, particularly the one who has inspired a life-changing experience through The Ruby of Badakshan. I must confess that this book of yours has single handily helped rejuvenate the faith in me and I am in debt of yours since. Thank you for your contributions.

Dear AA,

Very glad to hear from you. But even more to learn how important The Ruby of Badakhshan has been to your inner and outer life. Attending to both of these is Nasir Khusraw’s message.

Another time and fact to research, something of which I knew not. An intriguing wish and beautiful description: the humility of dress, a time of respect for nature. I look forward to reading her next book, or maybe more of her contributions on your website, or other websites. Now I need to go read more about this period in Ismaili history and about her own background.

What a picturesque account of the glorious event that demonstrates the richness of Fatimid Culture and contribution to civilisation.

Alice must be very fortunate to even imagine being with such intellectual giant as Nasir Khusraw. She has of course found enough information to make it all come alive for us. Thank you for sharing all this knowledge.

Dear Firoz, New Yorker, and Aziz,

Thanks very much for your comments. We, and history, are fortunate to have Nasir Khusraw as a witness to Fatimid Cairo and also as the embodiment of its values: to conduct one’s life excellently in all realms – spiritually, intellectually, materially, socially, artistically. That this is what being human means.

To learn more about Cairo, see the wonderful new book just published by the Institute of Ismaili Studies, called “Living in Historic Cairo,” edited by Farhad Daftary, Elizabeth Fernea and Azim Nanji. I have another article in there about Nasir Khusraw, but the entire volume is a splendid example of conjoining beauty and intellect and social conscience. Half the book is about the Aga Khan’s Cairo rehabilitation project.