“Itmadi Sabzali has served me in such a manner that after his death, I honour him with the title of a Pir” – Sir Sultan Mahomed Shah Aga Khan, 48th Ismaili Imam

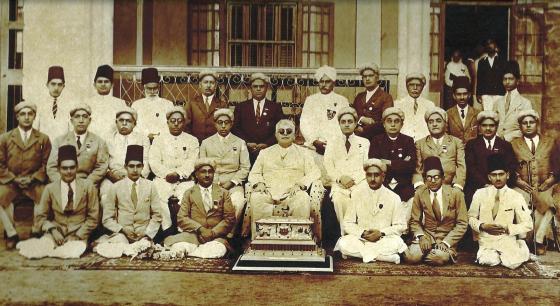

CLICK FOR A VERY GOOD ENLARGEMENT. This historical photo was taken in India in March 1936 on the occasion of the presentation of a casket by a group of Ismaili missionaries to His Highness the Aga Khan III to mark the occasion of his Golden Jubilee. Unless otherwise noted we may assume that all the persons in the photograph are missionaries. Back Row (l to r): Noorali Bandali, Gulamhusein Juma, Sayyed Mohamed Shah, Jaffer Jivan, Alidina Mamu, Ebrahim J. Varteji, Tajjar Mukhi Mohamed, Damji Velji, Abdulla Esmail and Badrudin Nurmohamed; Seated Centre row (l to r): Meghji Maherali, Husseini Pirmohamed, Alijah Moloo Allarakhia (casket donor), Chief Secretary Gulamhusein Virjee, President Alimohamed R Maklai, HIS HIGHNESS THE AGA KHAN III, President Alijah Esmail Mohamed Jaffer, Finance Secretary Tarmohamed Ravji, PIR SABZALI RAMZANALI (who at the time had the title Alijah), Jamal Virji and Hamir Lakha; Seated on carpet (l to r): Kassamali L Wadiwalla, Amirali Khudabaksh, Hajimohamed Fazalbhai, Mahmed Muradali, Madatali Rahemtullah Rajan and Juma Jiwa. Photographed by: Golden Art Studio; Photo: Ameer Janmohamed Collection, London, UK.

~~~~~~

Pir Sabzali (1871 – 1938)

Pir Satgur Nur, Pir Shams and other Ismaili Pirs from the 13th century onwards are credited with the conversion of large numbers of Hindus to the Ismaili faith, bringing them to the path of Satpanth (The True Path) – that of the recognition of the Imam of the Time. The holy writ of the Satpanth tradition, or the Nizari Ismaili Tradition in the Indo-Pak Subcontinent, is the collection of Ginans or hymns written by various Pirs. In this continuing series on Thank You Letters to Ismaili Historical Figures, author Ameer Janmohamed of London, England, pays his tribute to the Ismaili Pirs of the Ginanic tradition through a more recent historical figure in Ismaili history that he can relate to – the personality of Missionary Sabzali Ramzanali, who was bestowed with the status of a Pir by the 48th Ismaili Imam, Sir Sultan Mahomed Shah Aga Khan. During his lifetime, Pir Sabzali and his entourage visited the Ismaili communities deep in the Pamir mountains of Central Asia, far from home in India, buoyed by their faith in the Imam.

________________

5 May, 2012

Revered Pir Sabzali,

In all humility, this letter is a woefully inadequate attempt to express my reverence and gratitude through you, for all our Pirs from Pir Satgur Nur in the eleventh century, to Pir Shamsh, Pir Sadardin, and Pir Hassan Kabirdin, up to yourself, revered Pir Sabzali in the twentieth century.

We owe reverence and adulation to the Pirs for having attained this exalted spiritual status. For what can be greater for a Murid than being conferred the designation of Pir by the Imam of the time?

I personally express gratitude to the early Pirs for having introduced the Shia Imami Ismaili faith to my forefathers. I am what I am and where I am thanks to that single great decision one of my forefathers took several hundred years ago, when he embraced the Ismaili faith.

This is meant to be an expression of our eternal gratitude to our Pirs for having given us the great legacy of Ginans. We invoke their names and raise our hand to our forehead as a mark of reverence and submission each time their names are mentioned either as authors or as the inspiration for the Ginans.

As Ali Asani says in his book Ecstasy and Enlightenment:

“Although initially associated with the preaching of Ismaili doctrines and ideas, today, several centuries later, Ginans continue to exercise significant influence on the religious life of the Nizari Ismailis, not only in the sub-continent but also in other parts of the world where they have immigrated.

“When Wladimir Ivanow, the Russian Orientalist, was conducting his researches on the Ismailis of India in the early part of the 20th century, he noted ‘the strange fascination, the majestic pathos and beauty’ of the Ginans as they were being recited, and observed further that their ‘mystical appeal equals, if not exceeds that exercised by the Coran on the Arabic-speaking peoples.”

I can vouch for this ‘fascination, the majestic pathos, the beauty and the mystical appeal’ from personal experience. I say this because one of the more sublime and inspirational aspects of our religious practices for me has been our Ginan culture. Perhaps it is to do with linguistic affinity. I pray in Arabic and I know enough Arabic to know what my prayers purport. But instinctively and culturally I relate more closely with Ginans because the ‘Indian’ in me enables me to appreciate the nuances, subtleties and the occasional poetic licence incorporated in the verses which make up our Ginans.

Reciting Ginans in Jamatkhana differ from other public recitals. There is no musical accompaniment. Jamati participation depends on choice of Ginan. The Jamat joins in the refrain at the end of each verse. At the end of a recital, there is no way of judging audience reaction. Notwithstanding that, one feels instinctively when a recital has been good. I do believe that there are few moments more precious and fulfilling than listening to a Ginan well recited in the proper raga and dhab in a Jamatkhana.

Will it always remain thus, one wonders. Probably not, one fears. More and more of the second and third generation of Indo-Ismaili children are beginning to forget their mother tongues. They now ‘think’ in English, Portuguese, and French, etc., depending on where the diaspora has taken their families. Thus, direct access to our Ginans in their original forms is denied to them. And even more tellingly, they appear to be having difficulty in handling numerous Indian consonants; consonants which have always been beyond the capacity of European and African vocal chords.

They now learn Ginans from books with English phonetic spellings. And for meanings they need to refer to one of numerous books with Ginan translations. One of the finer specimens is A Scent of Sandalwood by Aziz Esmail. The book contains Ginans translated into English, their history and accompanying notes. To the uninitiated they may well read like English poetry. But the author makes it clear right from the beginning:

“One stark fact stares one in the face. I am only too acutely conscious of how pale and weak the English renditions are in comparison to the haunting, uplifting, hypnotic musical wealth of the original. Mine is the indistinction of a messenger attempting in vain to recapitulate a message originally heard live. In relation to the original, the translation is an anaemic facsimile. If I have decided to let it see the light of day, it is in the belief, justified or not, that an anaemic facsimile is better service to those who have an interest in this literature but cannot read the original, than none at all.”

It is staggering to consider that Pir Shamsh came as a foreigner to a new land in the time of Imam Kassim Shah (1310/1370). He and Pir Sadardin and successive Pirs mastered Urdu, Hindi, Gujarati, Sindhi, Punjabi, Cutchi and Khojki to an extent where they could communicate fluently, in prose and verse, with inhabitants of various regions on the sub-continent in the vernacular. They disseminated knowledge or gnan in the form of devotional hymns we call Ginans, and most astonishingly, for people of non-Indian origin, set many of these Ginans to Indian classical ragas. These Ginans in their timelessness have endured, and in their content and musicality, are as valid today as they were when first written.

The Pirs demonstrated amazing perspicacity and adaptability in their delicate quest to convert locals. Their mastery of the languages had enabled them to familiarise themselves with the tenets and practices of Hindu religion. They would have sensed that incorporating some form of continuity both in the essence and the practice of the new faith would make the change less traumatic and more palatable for the convert. Relating Hazrat Ali to the tenth Nakalanki Avatar is a prime example. Inclusion of names from The Ramayana and The Mahabharat in our Ginans further reinforce this.

As Tazim R. Kassam writes in her book Songs of Wisdom and Circles of Dance:

“Ginan recitation in the daily communal services of the Satpanth Ismailis represents a long tradition of liturgical prayer. The religious meaning of these hymns is centred in their ritualised performance. Religious benefit is accrued by the actual vocalisation or recitation of a Ginan, and thus, it is uncommon for a book of Ginans to be silently read in prayer. In the context of Satpanth practice, Ginans come to life when they are sung, and to sing a Ginan is to pray. Singing is thus ritualised into worship, a characteristic feature of the religious setting of India.

“The Ginan of the Ismaili pir is the Satpanth counterpart of the Hindu geet, bhajan or kirtan and forms a continuum in the expressive and inspirational aspects of the North Indian Sant and Bhakti traditions in the context of which poetry, melody and communal worship fuse to create religious ardour.”

It has been noted that although the Pirs of the time were of Persian origin there is no record of a single Ginan in Farsi.

Scholars agree that there are not enough written records to support what has always been an oral tradition, and a lot of stories have been handed down from one generation to the next. This makes for occasional uncertainty about exact periods and provenance.

I particularly love the story I was told a long time ago about Pir Sadardin. According to this story, Pir Sadardin undertook a long and arduous journey back to Iran to inform the Imam that there was now a Jamat in India who had embraced the faith and yearned for Didar of the Imam. Imam Islam Shah apparently instructed him to return to India, to make this his life’s work, and to establish places of worship for the new Jamats. Pir Sadardin returned to India and the first Jamatkhana was established in Sindh. Head of the congregation was called Mukhi, perhaps a derivative from the word mukhya, which means main or principal, and according to the legend the first Mukhi was a Sindhi Ismaili by the name of Sheth Trikam. From about that time Ismailis also began to be known as Khwajas, later Khojas.

This first Jamatkhana could well have been in Karachi in the province of Sindh. Once in 1920 Pir Sabzali, you Sir, were trying to organise the first ever All India Khoja Ismailia Conference. According to Mumtaz Ali Tajddin Sadik Ali, you were told by Mawlana Sultan Mahomed Shah to “Arrange it in Karachi. Not only it is my birth place, but also because Pir Sadruddin also arrived from Uchh Sharif and operated proselytizing mission from Karachi at first.”

“I Wish I’d Been There,” I have once expressed in the past when discussing the “Faith of my Forefathers,” for I have awe and wonderment for that particular moment in time when, thanks to our Pirs, along with others, my forefathers joined the faith.

I have taken the liberty of addressing this letter to you revered Pir Sabzali because you are a Pir of my generation and I can personally relate to you at several levels. I have been in your august presence in Mombasa and Nairobi more than once, without appreciating it, for I was but a mere child at the time. You stayed at the Nyali bungalow of Kassam Khimji during your visit to Mombasa in 1934 and members of my family were in your attendance. My Motabapa Manji Janmohamed, Nairobi Council President, had the honour of working with you in 1937 in preparing for Imam Sultan Mahomed Shah’s Golden Jubilee in Nairobi. My Fua Gulamhusein Mohamed Nasser Jindani was one of your principal associates in the formation of the Jubilee Insurance Co, following the Golden Jubilee celebrations.

Kisumu Council President Hasham Jamal had the honour of hosting you at his Kisumu residence in 1937, and somewhere in the Jamal family archives is a photograph of you carrying one year old Zeenat (who is now my wife) in your arms as the first grand-child of the President of the Kisumu Council.

Mumtaz Ali Tajddin Sadik Ali has the following to say in his biographical account of your glorious life (1871 -1938), published in 101 Ismaili Heroes:

“Mawlana Sultan Mahomed Shah said: ‘Itmadi Sabzali has reached God’s mercy. I give my blessings for him. His name will always remain immortalised in history. He was a chief dai of the present jamat like the dais of the past, and glorified the Ismaili faith in Africa, Sind, Punjab, Gwadar and India. Itmadi Sabzali was the standard bearer of the haqiqi momins. He departed from the world, putting the world in great loss. He has gone into the real bliss. It is a matter of happiness that he has no worldly problem till last breath of his life’.”

On December 15, 1938, the Imam said:

“The photo of late Itmadi Sabzali be placed in the Jamatkhana. His photos also be kept in the Jamatkhanas of Karachi, Punjab and Sialkot.”

On January 18, 1939, the Imam made the following historical announcement:

“Itmadi Sabzali has served me in such a manner that after his death, I honour him with the title of a Pir. If others would render such services, they too shall secure a like status. During the stretch of 54 years of my Imamate, to only one Pir Sabzali, I honour such a status”.

Mashallah.

I conclude with this admonition from Pir Sadardin:

Pir na bodh Ginan, vichari jene bhed na paya,

Ene ghafale te janama haraya ji

Tene papiye fokat fera khaya ji.

He who fails to comprehend the essence of Pir’s wisdom and guidance,

that erring mortal will have squandered his birth,

and the sinner’s incarnation will have been in vain.

In all humility,

Ameer Janmohamed

London, England.

______________

Copyright: Ameer K. Janmohamed/Simerg, May 2012.

Writer has lived lived life to the fullest

About the Writer: (Alijah) Ameer Kassam Janmohamed is the author of A Regal Romance and Other Memories and the three volume set of of AKJ Collection of Cynical Wisdom. His wonderfully written A Regal Romancepublished in London in 2008 by Society Books, is a rich tapestry of vividly told personal and family vignettes from 19th century onwards as well as insights of life in Kenya before and after independence. Mr. Janmohamed has a vast record of services to his credit. He was initiated into the Rotary club in Mombasa when he was a youth, and subsequently got elected as President and later as District Governor of Rotary International, a position which covered nine African and Indian Ocean countries. He continued to be involved with the Rotary after he moved to London, UK, in 1973, and acted as the President of the Kensington Club in 1981/1982. Today, he is the oldest surviving member of this chapter.

Within the Ismaili community he has served as a past Governor of the Institute of Ismaili Studies and director of the Zamana Gallery, both in London. In Mombasa, he served in the capacity as Kamadia and Mukhi of the Chief Jamatkhana between 1962 to 1966, and later served as the President of the Mombasa Provincial Council from 1968-1971. He was also a director of the Diamond Trust. He is an alumnus of the Aga Khan High School, Mombasa.

Readers are invited to read the following fine pieces by Alijah Janmohamed on this website:

1.The 1955 “Jubilee Ball” of His Highness the Aga Khan III at the Savoy

2.1953-1957: Ismailia Social and Residential Club and Jamatkhana at 51 Kensington Court, London W8

3.The Review Process and Presentation of Recommendations to Mawlana Hazar Imam for a New Ismaili Constitution in Africa

4.The Faith of My Forefathers contributed for Simerg’s special series I Wish I’d Been There.

_______

Further on-line resources:

_______

We invite your contribution for the thank you series. Please click on Thanking Ismaili Historical Figures to read about the series and links to published letters.

Share this article with others via the share option below. Please visit the Simerg Home page for links to articles posted most recently. For links to articles posted on this Web site since its launch in March 2009, please click What’s New. Sign-up for blog subscription at top right of this page.

We welcome feedback/letters from our readers on the essay. Please use the LEAVE A REPLY box which appears below. Your feedback may be edited for length and brevity, and is subject to moderation. We are unable to acknowledge unpublished letters.

I am Mumtaz Ali Tajddin Sadik Ali from Karachi. I have made my own website, containing Ismaili ceremonies, history of the Imams and Ismaili Pirs and my own waez/lectures. It contains all those materials which are much more needed to the young generation. My website is http://sdrv.ms/QpoOQ2

Thank you and Ya Ali Madad

Great piece with lots of invaluable historical information. In the picture I recognized my dad Missionary Madatali Rahemtulla Rajan Nanjee, seated directly in front of Pir Sabzali. He passed away in 1996 in Calgary at age 83. Keep up the great work – many thanks

Dr. Zul Nanjee

Guelph, Ontario

I am also alumnus of the Aga Khan High School, Mombasa (1959-1962). Amir Janmohamed’s letter is of great interest and it helps me better understand role of Pirs so far as Ginans and impact of “Ginanic Practice” is concerned. A few weeks back, here in Luanda, Angola, I heard my first Waez in Portuguese. I had raised a question with Missionary Re: Pirs and their linage,e tc. Hence this letter for me personally is very informative. Being in a mulit-lingual Jamat (Portuguese, Indians, East Africans and members from other parts of the world), I can say that the common link in our practice here, is “The Wonderful Tradition of Ginans”. Even in the Waez relayed in Portuguese, Ginan helped everybody relate to the Waez even if they did not understand Portuguese. No matter how young or old or what language the Jamati Member speaks: Ginans binds us all and it is relayed the same way no matter who and from where. We owe this to our Pirs.

Very nice piece as usual by Ameer Janmohamed. His knowledge ranges over religious as well as secular topics. He is one of the great reciters of ginans – qualitatively as well as quantitatively. I have heard him at the Mombasa Kuze jamalkhana and in one of his previous articles he had given a count of how many times he had recited ginans and in how many different countries. One point he makes is ginan-reading and -reciting is a dying thing as the younger generation do not know how to read Gujarati and do not understand it. They make a mess of the “n”, the “d”, and the “r” that are used in replacement of the difficult Gujarati consonants. I doubt anything could now be done to reverse the trends. Not all of us know Arabic, except for the translation of the verses in the dua. English is totally inadequate in its range as is clear from the recitation by the Kamadia does at the end of the two prayers.

Editor’s note: Izat Velji has responded to Ameer Janmohamed’s “Thank You” letter with her own piece, reminiscing Meghji missionary and Pir Sabzali. Please click https://simerg.com/thanking-ismaili-historical-figures/ameer-janmohameds-thank-you-letter-to-pir-sabzali-and-the-ismaili-pirs-of-the-ginanic-tradition/reminiscences-of-two-great-ismaili-missionaries-pir-sabzali-and-meghji-missionary/

Thank you for this piece of wisdom.

Thank you, Ameerbhai, for this valuable piece. You do have the gift of presenting the Ismaili history in a most interesting and lucid manner. Hope you will continue this good work for the benefit of all.

Beautiful. Just beautiful.

Indeed, this series has become not only for THANKING, but also an important informative and cultural series.

A beautiful recounting of a major figure in our Ismaili history who will not be forgotten for his services to our Beloved 48th Imam. Pir Sabzali will be remembered as one of the modern greats. And as a young person reading of his achievements it fills me with hope that we, the youth, should strive to continue to serve the Imamat with such love and dedication to our Imam-e Zaman. Peace and blessings to Pir Sabzali and all our Holy Pirs. Alhamdulillah.