“That Which Defeats” (Kileme) is what the Wachagga people traditionally called Mount Kilimanjaro. Whereas the deceptively gentle slope of Africa’s highest elevation looks easier to climb than steeper peaks, it regularly defeats physically fit individuals equipped with 21st-century gear and supported by teams of guides, porters and cooks. 30,000 eager souls from around the world attempt to scale “Kili” annually but altitude sickness, dehydration, and exhaustion prevent many from reaching the summit. The dormant volcano’s most powerful weapon is psychological — it tricks the human mind into surrendering. Compared to the 90% success of those leaving from the Mount Everest Base Camp, only 45% from Kilimanjaro’s Base Camp make it to the top. Around ten people die on Kili every year.

Article continues below

In pushing themselves to their extremes climbers become sharply aware of their relationship with nature and life itself. The attempt’s enormous exertion involves an intense engagement of the entire human being — body, mind and spirit — regardless of whether one reaches the summit. The words of Aga Khan III, Imam Sultan Mohamed Shah, resonate with this experience:

“Struggle is the meaning of life; defeat or victory is in the hands of God. But struggle itself is man’s duty and should be his joy.”

Dedicated and persistent striving enables perceptions of deep, concealed truths about oneself.

Today, as I gaze at Vancouver’s North Shore Mountains, my thoughts turn back to December 1973 when Kilimanjaro itself taught me how to ascend it. Fifty years later, I still strive to understand the enigmatic experience during which the mountain forced a humbling introspection. Kili crushed my 17-year-old self’s delusions and repositioned my attitude towards nature to make the ascent possible. The event became a landmark on life’s uneven terrain and a point of re-orientation during times of difficulty.

Stumbling Upon Arrival

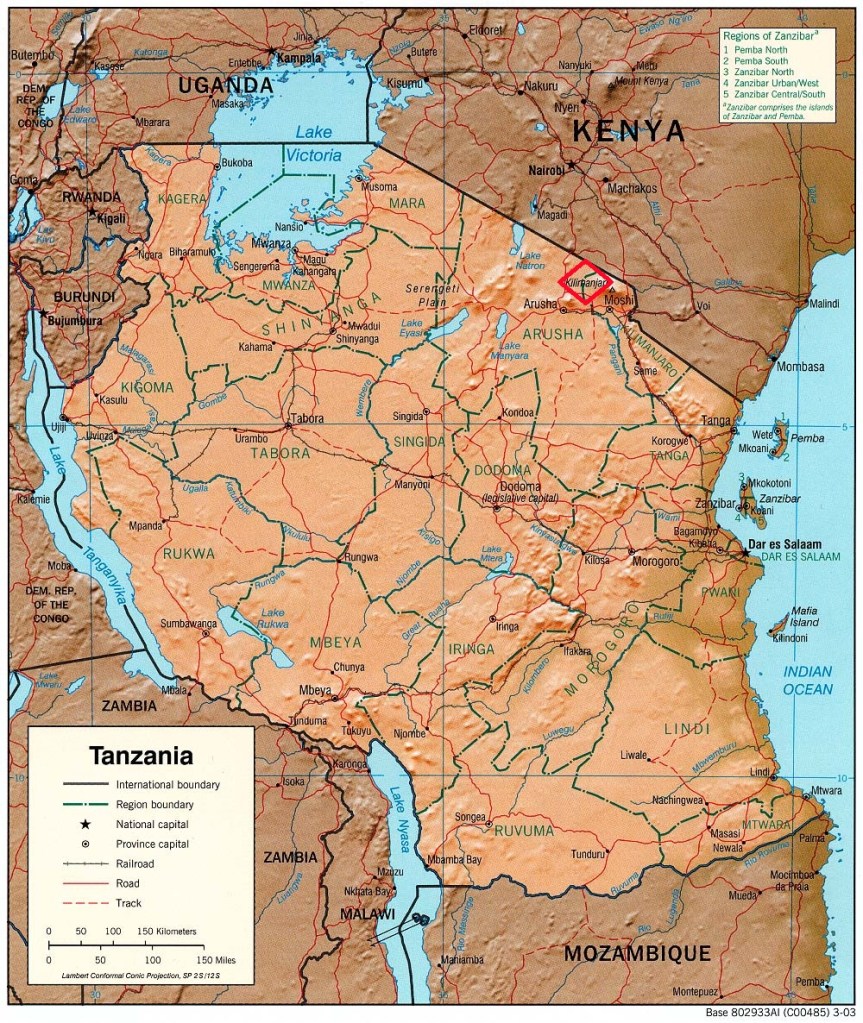

Eruptive activity 2.5 million years ago in the Great Rift Valley began forming the world’s highest free-standing mountain above sea level. Three volcanic cones, Kibo, Mawenzi and Shira, crown the colossus that geographically covers 1,000 square kilometres and from base to summit holds five eco-climatic zones (cultivation, forest, heather-moorland, alpine desert, and arctic).

Article continues below

Mountains hold a universal mystique and to some, they beckon as a personal challenge. Aga Khan High School, which I attended in Nairobi, had held annual mountain-climbing trips for senior students, but these ventures had been discontinued by the time I reached the upper levels.

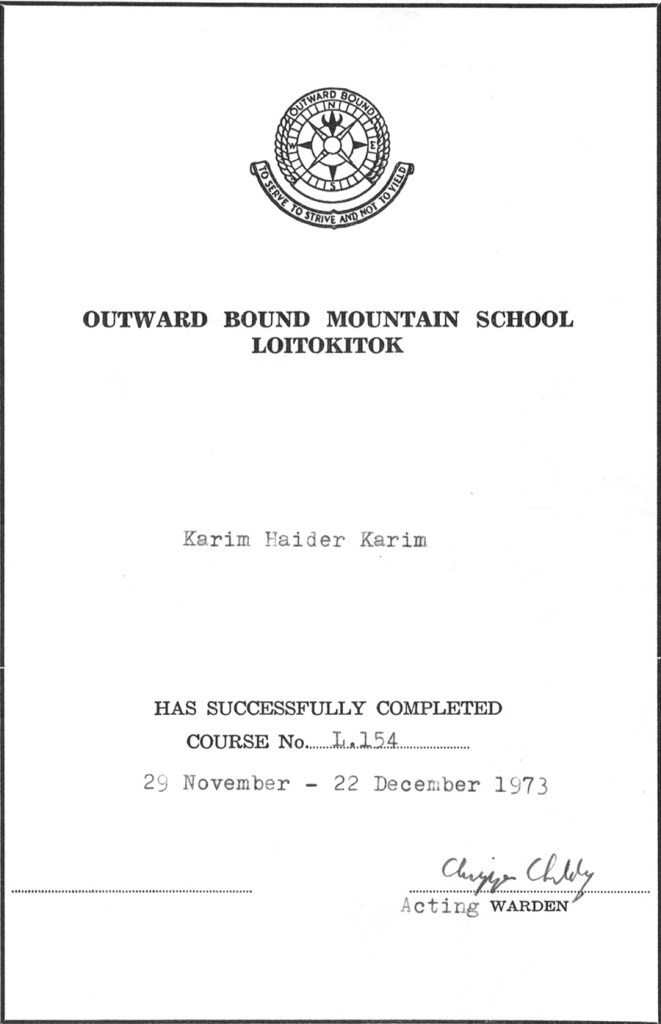

Some students looked to the Outward Bound Mountain School of East Africa, whose brochure said that its strenuous 23-day courses, including Kilimanjaro climbs, were “based on a spiritual foundation” and as an opportunity for self-discovery through self-discipline, teamwork and “man-management.” The school’s motto, “To Serve, To Strive and Not To Yield” is adapted from the line in Tennyson’s poem Ulysses, whose original wording reads: “To serve, to strive, to find and not to yield.” Ironically, it was “to find” that was vital to my Outward Bound experience.

Article continues below

Alexander Pope, another poet, famously remarked that “fools rush in where angels fear to tread.” How foolish I was, never having climbed so much as a hill or gone camping, to think that I would tackle Africa’s highest mountain. Whereas my athletic performance in my early secondary years had been above average, the high school’s physical education program was non-existent at upper levels. I had become used to the comfortable and spoiled life of a middle-class South Asian teenager in a household where African servants did most of the physical labour. Even the doctor who provided my fitness certificate to attend Outward Bound was somewhat skeptical, but that did not spoil my dream of reaching Africa’s summit.

The Outward Bound campus occupied 27 acres on the Kenyan side of the Kilimanjaro rain forest near the small town of Loitokitok in Maasai country — a bumpy four-hour bus ride from Nairobi. Excited would-be mountaineers were dropped off for Course L154 held from November 29 to December 22, 1973. The contingent was met by instructors who told us to embark immediately on a cross-country run. I jogged along with the group but, after a while, could not keep up with the bigger, fitter colleagues. My lungs strained, and though I strove to push myself it wasn’t long before I found myself gasping on the ground. The goal to be at the mountain’s top had stumbled at its base. I looked up at Kilimanjaro and the large Kibo peak seemed to be mocking me.

Article continues below; click on map for enlargement

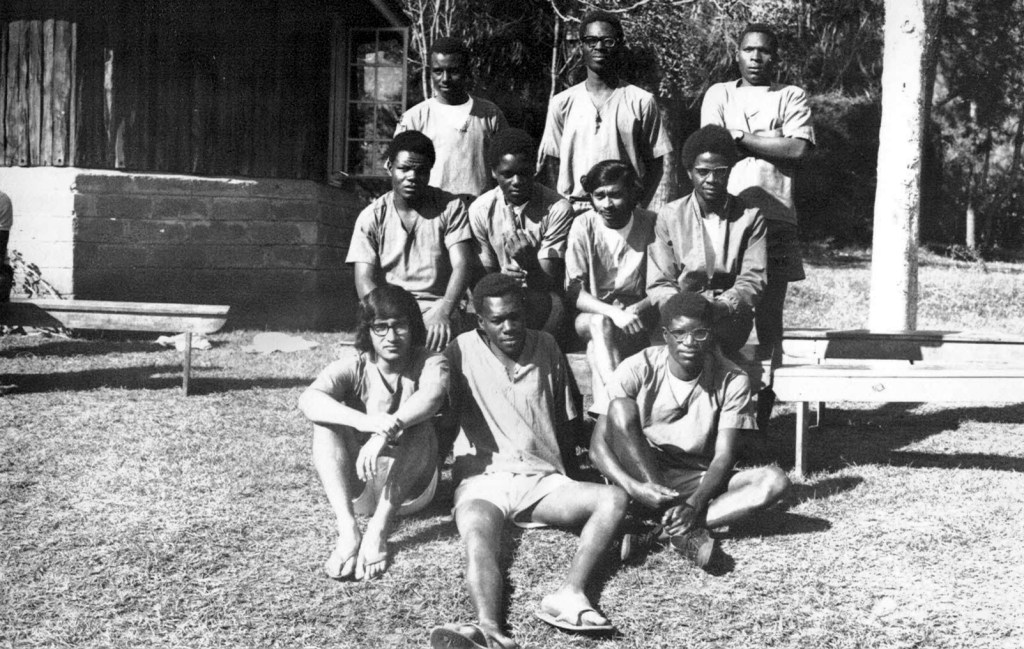

Students were assigned dormitories according to designated “patrols.” Kenya, Uganda and Tanzania had been allocated 20 participants each, but something was lost in translation and the Tanzanian coordinator sent 60. Rather than send 40 back, the British warden decided to let all stay and the course was hurriedly reconfigured into two sections, whose activity schedules were staggered. Consequently, students in my section were given little preparatory training before they were sent up the mountain for the Solo Expedition. This did not bode well.

The Pangs of Failure

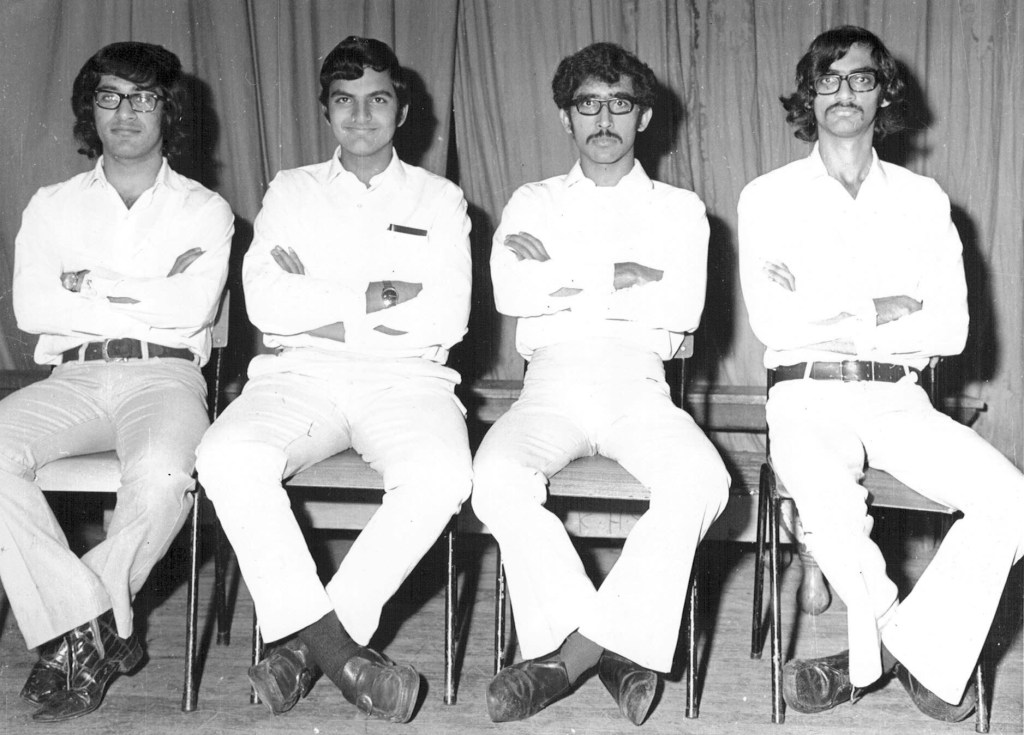

The course’s students were all Africans except for three South Asians and most of the instructors came from the US with a few from Tanzania and Uganda. Additional patrols were formed due to the unexpectedly large contingent and assistant instructors were put in charge of some patrols including mine. Participants were assigned responsibilities; I was appointed quartermaster, responsible for distributing supplies.

Article continues below

The Solo Expedition involved a trek up to the altitude of 12,000 feet where each student spent a night alone on the mountainside. This major activity was normally scheduled for the course’s fifth day, but our section had to embark two days early. Nonetheless, we excitedly started our trek up Kilimanjaro, crossing the border into Tanzania, going past farms and into the rain forest. As the heat and humidity pressed on us in the early morning, a blur of black and white fur suddenly appeared on tall trees — it was a Colobus monkey swinging over us. We wondered how many other animals watched our contingent passing through their territory.

Vegetation became sparser and the air got thinner and cooler as we climbed higher into the heather-moorland zone. Rucksacks felt heavier at the sharper incline and feet began to slip on the rocky terrain. Most carried around 40 pounds of weight but I had unthinkingly over-packed mine and was taking frequent breaks, which slowed the patrol down. Then, without saying a word, one person took my bag and distributed several of its contents among the patrol as I, the quartermaster, sat on a rock feeling very embarrassed. (I learned later that such an experience was not uncommon in Outward Bound courses.)

The patrol reached its destination in the late afternoon. We were to spend the night alone on the rocky slope half a kilometre from one another. Each student had only a few food supplies, three matchsticks and a well-worn sleeping bag. The instructor designated our respective spots on the mountainside, and I resolved to put the day’s humiliation aside to make the best of the situation.

Article continues below

Looking upwards, Kibo’s snowy peak gleamed closer than ever before and on the other side was the vast mountainside sloping downwards. It was getting dark, and I set to gathering firewood. Never having made a campfire in my life, I diligently assembled a pile of sticks that would warm me in the night. With the wood and kindling arranged in a neat pile, the fire was all set to be lit. The evening sky was clear except for the small clouds that were swiftly riding up the mountain and through my small campsite. I struck the first match and put it to paper to start the fire. The flame fizzled out as soon as it touched the kindling. No matter, I told myself — there are two more left. The second match also went out at the paper. Only one remained. My hands trembled and I began to pray. But no success again. What went wrong? I realized that I had been foiled by the innocent-looking clouds that had moistened the kindling. My spirits dampened as I set to spend the night on the cold and desolate mountainside with no fire to warm me or my food. The hazy half-moon also gave no comfort. I looked up at Kibo and it seemed to be laughing at me again.

When the patrol reassembled the following morning for the descent, it became apparent that almost everyone had had a difficult time. We trudged downhill, arriving at the school late in the evening. My confidence was severely depleted, and I was overcome with a sense of failure. Many Outward Bound participants experienced mental distress at this stage of the course, but the possibility of escape from the isolated school was slim. The bus came to Loitokitok once a week and communication with the rest of the world was only by a ham radio in the warden’s office. “Warden” indeed! We had found ourselves to be in a prison.

Daybreak at the school began with a cross-country run followed immediately by a plunge into the freezing swimming pool. This rapid hot-cold transition increased the body’s haemoglobin to enhance oxygen intake at high altitude. Participants engaged for some two weeks in various forms of training and activities (which are amply described in the book Kilimanjaro Outward Bound by Salim Manji). The anticipation of the impending climb to Kili’s summit was constantly in our minds and from time to time, we stared at the peak in the distance, wondering about the challenges that it would hurl at us as we attempted to scale it.

The Final Expedition

Sixty students and instructors set out in the week before Christmas for the Final Expedition, taking the Rongai Route on Kilimanjaro’s northern face as we had for the Solo Expedition. Private sector package trips along this way took six to seven days. On Outward Bound’s schedule, the climbers carrying their own loads endeavoured to reach the summit on the third morning and return to the school after spending another day descending.

The course’s activities were designed to toughen students physically and mentally, but a sense of failure from the previous ascent weighed heavily on me. Nonetheless, the aspiration to make it to the top was still very much alive. I had figured out how to climb better and gained more confidence as we rose above the level of the Solo Expedition, but the going got harder as the oxygen thinned. Ultraviolet exposure at high altitude peeled the skin off my face. Objects looked and felt strange. The alpine desert zone, strewn with sharp-edged reddish rocks, appeared like terrain on Mars. An airliner flying near the peak to give passengers a closer view seemed like a surreal sight. I asked a senior instructor during a break whether it was physical or mental preparation that was more important for the climb. He replied that “mental fitness helps you draw on untapped physical resources.” I gazed at Kibo and it seemed to smile.

Article continues below

We reached the base camp on the second afternoon. The large, rugged Outward Bound Hut sat on the desolate rocky saddle between Kibo and Mawenzi peaks at 15,469 ft (4,715 m), where the barren environment’s only visible life was our group. It became dark and cold quickly as the sun passed behind the mountainside, which was now an enormous presence. We slipped into our sleeping bags early as the remaining 4,000 ft ascent was to begin at 2 am. It seemed that we had hardly slept when the instructors roused us. I noticed in the dim light that some water that had spilled from a container near my head and had frozen on the floorboards.

Scaling at nighttime is a vital tactic to improve the chances of reaching Kibo’s summit. Many climbers fail because the slope’s convex shape makes the summit seem closer than it really is. The mountain’s cap remains hidden by the terrain’s curve and as hikers approach what they think is the top they realize that there is more to go. The disappointment hits people repeatedly, and they feel increasingly disheartened. It is in this way that Kili mentally defeats many able mountaineers who make it this far. Attempting the final ascent in pitch dark helps prevent climbers from succumbing to Kibo’s deception.

It was impossible to walk straight up the slope as feet sank into screes — the masses of loose, little stones that cover the peak — so we snaked on the slope in long zig-zag lines. After some time, several colleagues began to fall prey to severe altitude sickness, dehydration, or exhaustion and were forced to turn back. Others pushed on. We had been hiking for four hours under the starry sky when it started becoming brighter and the sun inevitably rose. Looking up, we saw the visible edge of the mountain meet the sky and imagined that we were close to the summit. But this was a mirage: despite walking on and on we would just not arrive. The curve ball that Kibo was throwing at us played havoc with our minds and deeply frustrated climbers surrendered one after another.

Article continues below

One-third of the group remained. It was harder to lift our legs because our boots were partially buried in the screes, and we advanced only one step for every three steps that we took. I looked up to find Kibo’s snowcap, but it was not visible from our location on the slope. How close was it? How much more to go? I prayed to find a way for me to reach the goal. To serve, to strive, to find and not to yield.

My mind appeared to slide into a kind of trance and the pain, the exhaustion and the endless climb’s futility slipped out of consciousness. Nothing seemed to matter. I even disconnected with the aim of reaching the top. Nevertheless, the body continued to move forward — but with little awareness of motion. One foot went in front of the other, on and on and on. It seemed that the intense struggle had dimmed the perception of physical agony and mental anguish, and my being had found a way to ignore completely the urge to stop.

When body and mind recede, spirit comes to the fore. Kilimanjaro had battered me for almost three weeks, putting the body through punishing challenges and the mind through deep feelings of frustration and failure. It seemed that I had asked the instructor the wrong question about physical or mental preparation on the previous day because the mountain regularly defeated people with superior physical and mental training. It turns both body and mind into one’s enemies. How was it then that I had survived to this point? It seemed that Kilimanjaro itself was the instructor that had shown me gradually, through a series of defeats, how to tackle the biggest challenge. The failures of body and mind had induced me to look for a way beyond them. Instead of trying to conquer the mountain, I had to have the humility to learn from it. Rather than obey my own body and mind’s command to surrender, my being instead had to turn to nature and bow to it. With that submission, Kili itself lifted me.

It felt like an anti-climax to arrive at Gilman’s Point after what seemed to be an interminable journey. Standing at 18,885 ft (5,756 m) it is one of Kilimanjaro’s three summits, the other two being Uhuru and Stella. With my name written in the book kept in a wooden box, I continued with the remaining climbers towards Uhuru Point, the mountain’s highest spot (19,341 ft / 5,895 m), which was 139 meters higher than Gilman and a 5.5 km trek around Kibo’s volcanic rim. My mind continued in a trance-like state. Although I had never previously been near snow, I did not even notice it around me on the Arctic-zone summit. My body seemed to have reached extreme limits, but it kept walking. At one point, when an instructor helped me up after I had collapsed with utter fatigue onto a boulder, my frame immediately resumed walking as if it were a programmed machine.

Thick clouds had gathered ahead on the volcano’s ridge. Instructors assessed it too dangerous to continue and decided that the group had to turn back. There must have been some human emotion left in me because I felt the disappointment of not reaching Uhuru, even though climbers making it to Gilman are formally considered to have scaled Kilimanjaro. The descent took one day and there were blisters on the soles of my feet by the time we made it to the school. Many were surprised to hear that I had made it to the summit.

Article concludes below

On the course’s last day, students went on a final daybreak run and plunge, the warden presented certificates and we said our goodbyes. My mind tried to process the Outward Bound experience on the bus trip back to Nairobi, but it was overwhelmed. Kilimanjaro had put me through a profoundly humbling process of self-realization. I seemed to be in a state of shock, from which it took months to recover. Half a century later, I have finally been able to write about the 23 days in 1973 that made a life-long impact.

Date posted: December 27, 2023.

_______________________

We welcome feedback from our readers. Please click LEAVE A COMMENT. Your letter may be edited for length and brevity and is subject to moderation.

About the author: Karim H. Karim is Chancellor’s Professor at Carleton University. He is an award-winning author and the Government of Canada has honoured him for his public service. Dr. Karim has served as director of Carleton’s School of Journalism & Communication and its Centre for the Study of Islam as well as of the Institute of Ismaili Studies. His publications can be accessed at Academia.edu.

Excellent Article – Brought back many memories of the Outward Bound experience… Thanks for Sharing

An inspiring story of how endurance, humility and a spirit of submission overcomes the limits of mind and body.

My dearest Malik Bhai & Dr. Karim.

What a wonderful trip down memory lane! I have read and reread this article thrice. I too had that dream of going to Outward Bound school in Loitokitok and climbing Kili when I was eighteen, but that dream did not materialize then, but NEVER died.

In 1998 ( when I was 51), I attended The Canadian Outward Bound Wilderness School in Georgian Bay, Ontario and climbed Kili in Aug 2000. We took the Marangu route and made it to “Uhuru Peak” at sunrise. Kibo to Uhuru Peak was the hardest, but most memorable. Never let a dream die…

Love, Light & Cheers Muslim Harji

“PRAYER WITHOUT ACTION IS JUST NOISE”

Beautifully written article. Although Nairobi is my home town I did not know much more than sheer name ‘Mount Kilimanjaro’. What a shame!

Professor Karim was and surely is a brave adventurous person. He has made me realize how good the Agha Khan has been to the world by providing opportunities to improve personal skills.

Many thanks Professor Karim for enlightening me about the great mountain and the energetic individuals who tackle difficult assignments. Well done SIR and many thanks for sharing such in informative experience. I wish I had attended the Agha Khan school rather than the Duke of Gloucester school to take advantage of the opportunities to know how to tackle difficult challenges of the world.

Many thanks again Professor Karim.

This posting in Simerg allows me the opportunity

to pay tribute of a different kind to Professor

Karim H. Karim who is a humble outstanding

scholar of Ismaili Studies, of which I have been a

student most of my life. Therefore I have followed,

with utter reverence, admiration and respect, the

works of both Ismaili and non-Ismaili authors. Last

year, he kindly accepted my invitation to join me

and members of my family for a private luncheon

to host Professor Faisal Dewji of Oxford University

during his visit to Vancouver.

Professor Karim is a fellow alumnus of Columbia

University, and I am blessed to be in his academic

shadow. Recently, I shared with him and a few others

my intention and itinerary to travel in the footsteps

of Mawlana Rumi, Shams Tabrez, and our Pirs of

Satpanth, immediately following an IIS course in

Tunisia entitled ‘In the Footsteps of the Fatimids’,

conducted by the renowned scholar and expert in

Fatimid studies, Professor Shainool Jiwa (of IIS and

Edinburgh University), of which he was very

encouraging and supportive.

Excellent article, Karim. Thank you for sharing your adventure.