Major excavation activities have been underway for the past few years resulting in interesting archaeological discoveries. Here we see the legendary water basin which filled itself up by collecting rainwater and melting snow from channels and canals on the mountains. Photo: Muslim Harji, Montreal, PQ, Canada. © Copyright.

PULLING BACK THE SILK CURTAIN

“The Nizari [Ismailis] excelled in the fields of theology, philosophy, architecture and science, but their opponents demonized them as bloodthirsty extremist religious murderers…The returning Crusaders brought back the legend of the pothead assassins, partly because they loved to believe imaginative romantic tales of the East…In 1256, Genghis Khan’s grandson, Hulagu, destroyed the Nizali mountain castles, one at a time. Their political and military power was permanently broken (although today, some several million Nizalis still survive in some 25 countries across Asia, Africa, Europe and North America).

Timeline by Dr. Ali M. Rajput, Birmingham, England.

“In 1273, Marco Polo visited Alamut, and brought back the story of how hashish was used to attract potential killers…After, Dante was the first to use the word “assassin” in the 19th Canto of The Inferno in his Divine Comedy. The word “assassin” remained in various European languages, right through to Dan Brown, author of the Da Vinci Code, who mentions the Assassins in his book, Angels and Demons. But there are a few reasons why the hashish-assassin myth is almost certainly wrong….If hashish is given in a large enough dose to cause unconsciousness, it will first cause nausea and hallucinations – which are usually very scary and unpleasant to the unsuspecting user.” — Excerpts from Dr. Karl S. Kruszelnicki’s “Hashish Assassin – Pulling Back the Silk Curtain”, broadcast on ABC Science Australia. Dr. Karl is Julius Sumner Miller Fellow, School of Physics, University of Sydney.

Photo: Muslim Harji, Montreal, PQ, Canada. © Copyright.

~~~~~~~~~

ETYMOLOGY

Nevertheless, the most acceptable etymology of the word assassin is the simple one: it comes from Hassan (Hassan ibn al-Sabbah) and his followers, and so had it been for centuries. The noise around the hashish version was invented in 1809, in Paris, by the French orientalist Sylvestre de Sacy, whom on July the 7th of that year, presented a lecture at the Academy of Inscriptions and Fine Letters (Académie des inscriptions et belles lettres) – part of the Institute of France – in which he retook the Marco Polo chronicle concerning drugs and this sect of murderers, and associated it with the word. Curiously his theory had great success and apparently still has…Jacques Boudet, in Les mots de l’histoire, Ed. Larousse-Bordas, Paris, 1998

~~~~~~~~~

THE TRUTH IS DIFFERENT

[…] their contemporaries in the Muslim world would call them hash-ishiyun, “hashish-smokers”; some Orientalists thought that this was the origin of the word “assassin,” which in many European languages was more terrifying yet….the truth is different. According to texts Hassan-i Sabbah liked to call his disciples Asasiyun, meaning people who are faithful to the Asās, meaning “foundation” of the faith. This is the word, misunderstood by foreign travelers, that seemed similar to “hashish” — Amin Maalouf, in Samarkand, Interlink Publishing Group, New York, 1998

~~~~~~~~~

Editor’s note: The following piece by Valerie Gonzalez has been adapted from her review of the book Eagle’s Nest – Ismaili Castles in Iran and Syria by the late Professor Peter Peter Wiley, who had spent nearly a lifetime discovering and investigating the Ismaili castles of Iran and Syria. Professor Wiley passed away on April 23, 2009, at the age 86. Valerie’s copyright piece originally appeared in REMMM (Issue 123|July 2008) and was reproduced on this blog in full (see link below) with the kind permission of Revue des mondes musulmans et de la Méditerranée.

DECONSTRUCTION OF THE MYTH

The Castle of Alamut, nested on the top of the colossal mass of granite rock, became the centre of Nizari Ismaili activity after the fall of the Fatimid Empire. It is not until you come to the foot of this colossal mass of stone that you realize the immensity and impregnability of the fortress at its summit. Photo: Muslim Harji, Montreal, PQ, Canada. © Copyright. Muslim Harji, Montreal, PQ, Canada. © Copyright.

By Valerie Gonzalez

Old myths are very difficult to deconstruct, even when historical evidence reveals the absurdity of their foundations. The infamous “assassin” legend that from the Middle Ages soils the memory of the Nizari Ismaili community is an example of this incorrigible defect of the collective consciousnesses. The image presented by both Christian and Muslim chroniclers of the Ismailis as unscrupulous terrorists is unfortunate if their sole fault lay in surviving as a distinct political and religious community within a hostile and troubled environment. The Crusaders, Sunnis and Seldjuk Turks naturally saw in this Shi’ite minority a threat to their establishment and expended great efforts in eliminating the Ismaili State from Iran and Syria. In addition to the pressures exerted by the great powers holding sway over the Middle East, in the 13th century, the Ismailis had to confront the Mongol threat which finally overwhelmed them. It is not wonder that in such a context they deployed the most efficient means of defense available to maintain not only the network of their strongholds and basis of their State, but also their faith and culture, the very sense of existence. In practice however, they were no more immoral or cruel than their contemporaries. They simply proved tremendously clever and obstinate in facing adversity and in struggling against forces vastly more powerful than their own. And it is probably for this reason that the Nizari Ismaili community were subject to demonization.

Attaining the summit at Alamut is a breath-taking and exhilarating experience. The fortress complex, one soon discovers, sits astride a dangerously narrow ledge of rock resembling the handle and blade of a knife. The above is an open passage through the mountain. Photo: Muslim Harji, Montreal, PQ, Canada. © Copyright

Much scholarship was required to unravel the dark mystery of the medieval Ismaili community. Numerous historical essays and archeological reports, among them Fahrad Daftari’s extensive works, have provided an accurate view of the Ismailis within the Islamic tradition. But assuredly the latest release on the subject, Peter Willey’s book Eagle’s Nest: Ismaili Castles in Iran and Syria, brings invaluable new insights by accurately portraying the environment in which the life and struggles of the Ismaili faithful took place. There is no question but that this book offers a convincing tool for the deconstruction of the false myths which surround the cult of the Assassins.

Far from being the addicts of hashish (the word assassin is believed widely, but incorrectly, to derive from the word hashishin) and a band of murderous brigands, the Ismailis were highly intelligent and devout Muslims serving their own Imam or spiritual leader (the present Imam is the Aga Khan) and attempting to build a new and vigorous Islamic state independent of the Seljuqs who had conquered Iran in 1038 – Peter Willey, Geographical Magazine, UK, February 1998

More than a mere treatise on the archaeology of the Ismaili castles in Iran and Syria, Willey’s book shows multiple qualities. As an academic work, it fulfills its main objective which is to present the results of a meticulous description and observation of these fortified sites. The considerable amount of information contained in the volume reflects a near life-time of research devoted to the subject. Not a single pile of stones or rubble has escaped Willey’s acute attention, or skillful restoration in clear prose of the forbidding grandeur of the Ismaili military architecture. Each remaining element of structure is analyzed and appropriately re-situated in the initial order both of the architectural organization of the building itself and of its broader setting within the coherent chain of fortresses spread over Ismaili territories. The material and documentation at the author’s disposal, including building scale, purpose, population levels and strategic importance have been patiently collected in order to present a reliable picture of the complex network of Ismaili strongholds. Maps, ground plans, photographs and even artists’ impressions and drawings complete the written work together with four appendices which include the castles’ inventory, a list of Willey’s expeditions and two catalogues of the ceramic and coin artifacts dating from the Alamut Period found at the site.

As seen on NASA’s Astronomy Picture of the Day and the National Geographic News, a meteor’s streak and the arc of the Milky Way hang over the imposing mountain fortress of Alamut in this starry scene. Photo: Babak Tafreshi/Dreamview.net . Copyright.

Beyond the high quality scientific report based on the archaeological record, Eagle’s Nest offers a brilliant reconstitution of Ismaili material culture from an historical, intellectual and sociological point of view, from the 11th century through the Mongol destructions of the mid 13th century. Willey restitutes the very meaning of the architecture he studies through the history of its builders and inhabitants, pointing out the most significant events of their lifetimes and portraying the great spiritual and political leaders of the Ismaili community. Methodically and surely, Willey describes the intricate historical background of the Ismaili State in which multiple powers confronted or fought each other, including Seljuk Turks, ambitious Sunni and Shii’a rulers, Crusaders on the Mediterranean coast, to propose his own interpretation of the historical evidence. Where evidence lacks or where persistent misconceptions require redress, the author proposes and defends critical hypotheses. The historical and cultural dimension of Willey’ archaeological investigation is particularly enhanced by the presentation of certain situations and events as literary narratives, as he does in the beginning of chapter 2, “Hasan Sabbah and the Ismailis of Iran”. The passage in question relates the capture without bloodshed of the Alamut fortress under Seljuk authority and begins thus: “It was nearly noon on a hot day in the early summer of 1090. Mahdi, the lord of the castle of Alamut, was beginning to sweat a little” (p. 21). In this way, the author makes us relive the extraordinary event in a human atmosphere that is quite uncommon in scholarly works.

A tribute to the great Ismaili dai, Hasan bin Sabbah who was responsible for establishing the Alamut state after the divisions in the Fatimid Empire led to its eventual demise. Hasan maintained that Imam Nizar and not Musteali was the rightful heir to Imam Mustansir billah, the 8th Fatimid Caliph. Photo: Muslim Harji, Montreal, PQ, Canada. © Copyright.

Willey’s sensitivity to humanistic values is perceptible throughout the book, not only through the telling of the past but also in the lively narration of the research trips themselves. First, he pays considerable attention to the actual environment of the castles he visits, their awesome natural frame and the rural or urban settings of the surroundings that are presented with delight and consideration. Although most of the time the Ismaili vestiges are ghost constructions in remote, isolated regions, they are not at all presented by Willey as still life portraits. Rather, each fortress is an element in a busy, human landscape. As an example, where appropriate Willey writes about agriculture and local conditions in the surrounding villages for fortresses located in rural areas. Also, the local population and individuals involved in Willey’s expeditions frequently are mentioned as actors in the archaeological narrative. In this way, Willey underscores the support of both his team and the local community in contributing to the success of his research. Particularly moving is his attitude toward the people who help him visit inaccessible locations under difficult conditions and various orders, especially his work partner Adrianne Woodfine. More broadly, the practical aspects of each journey, the general organization and unexpected situations and encounters are meticulously recounted so that the book offers the live texture of a human adventure together with its purely scholarly content.

It is often difficult to describe to friends the problems which the investigation of Ismaili castles present. They are built on the top of high mountains, covering the entire summit, and are normally surrounded by three defensive walls with numerous outworks. Most of the castles were destroyed by the Mongols and the ruins are dangerous and infested with snakes and scorpions on or under the stones or in the cracks of walls. The steep scree and sharp rocks are formidable, especially in the intense heat and altitude of over 2000 metres – Peter Willey, Geographical Magazine, UK, February 1998

Chapters 7 through 12 cover the various areas of the Iranian Ismaili strongholds. Willey naturally begins with the fortresses in the famous Alamut Valley of the Alborz Mountains, the fortress in which the infamous legend of the “Assassins” took place. Alamut fortress constituted the very heart of the Nizari State in Iran and was the seat of Hasan Sabbah. Alamut and its sister fortresses represented the epitome of Ismaili military science. Willey presents it with a rigorous method of sketching, measuring and enumeration of the construction’s features and structures, topography, architectural configuration, water equipment, cisterns, underground storage, garrison quarters and so on.

The pottery kilns in the valley of Andij in the Alamut valley. Some 15 kilns were discovered including good examples of contemporary ceramics. Photo: http://www.iis.ac.uk

The Alamut castle like many of the Ismaili strongholds contained facilities for religious activities and higher learning such as libraries. To support his observations, Willey quotes several times the Mongol historian, Juwayni, who witnessed the surrender of the Alamut fortress among other similar events. Although this chronicler was hostile to the Ismailis, his detailed reports offer an invaluable source of information. In particular he inspected the Alamut fortress’ interior prior to destruction and mentions, not without admiration, its remarkable facilities (p.100). Indeed, the sophistication of their architecture allowed the Ismailis to resist the fiercest attacks while ultimately succumbing to the formidable Mongol war machinery. Willey relates with great empathy for the desperate inhabitants the dramatic capture and systematic destruction of Alamut and other Ismaili strongholds. After Alamut, Willey investigates the other Iranian Ismaili castles of the regions of Qumes, Khorassan, Qohistan and in the surroundings of the Seldjuk capital Isfahan.

Willey terminates his book with a moving epilogue in which he shares a few of the thoughts, feelings and questions raised in his heart and mind by the exceptional fate of the Ismailis. He naturally mentions the remarkable endeavor of the Aga Khan’s organization for the development of both Ismaili and Islamic culture in continuation with the educational tradition of the community since the Middle Ages.

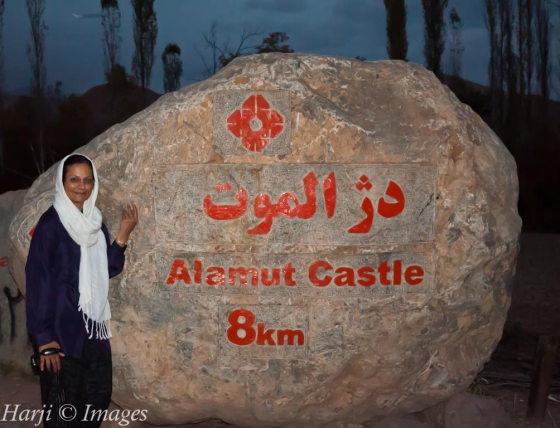

Nevin Harji stands by an official road sign when she visited Alamut with husband Muslim. Photo: Muslim Harji, Montreal, PQ, Canada. © Copyright

If, through such personal treatment, Willey hoped to clarify the historical issues surrounding Ismaili culture through the ages, he most assuredly succeeded. Eagle’s Nest unveils the extraordinary reality and humanity of the medieval Ismaili civilization, often hidden behind romantic images of remote ruins and the dark secrets contained behind crumbling walls. Finally, that Willey should communicate his deep affection for the countries he explored, particularly Iran, and the Ismaili themselves, is not the least quality of this book.

Date posted: December 14, 2015.

___________

Credits and notes:

1. The book review originally appeared in REMMM (Issue 123|July 2008) and was reproduced on this web site with the kind permission of Revue des mondes musulmans et de la Méditerranée under the title Voices: Unravelling the Dark History of the Medieval Ismaili Community

2. Eagle’s Nest: Ismaili Castles in Iran and Syria, by Peter Willey, published by I.B. Tauris, 2005, London – New York, 321 pages, hard back. Approximate prices in Canada, USA and the UK (at Chapters.ca $45.00 – $61.00; at Amazon.com $37.00 – $58.00; new at Borders.com $58.00, at Amazon.co.uk Pounds 9.95 – 21.25, note price range based on used – new book)

We welcome your feedback. Please click Leave a comment.

Very interesting background of the Alamut era. Thanks to the author Valerie Gonzales and others who contributed to the piece.

Very interesting read.