“The Spiritual Adam is to be identified with the divine Nur (Light) of Imamat, which is symbolised in the poem by the ‘glittering star of glory wrought and beauty spun’. The Mazhar par-excellence is the Imam who bears this Light in the terrestrial world. He is the most perfect expression of the divine hypostasis because in him the theomorphosis is fully realised and the Absolute becomes manifest to mortal eyes.”

Mazhar

By KUTUB KASSAM

(1944-2019)

I

Before and after

the notion and the conception,

after and before the ascent

and the descent,

before

the exhalation

and after the inhalation,

in the mirror of infinity appears

reflected without

being effected,

an oblique plane of

occultation,

a formless square

of un-differentiated,

impalpable darkness, without

sense perceived nor by cognition

conceived, in dreamless sleep concealed.

II

The darkness radiates

a boundless halo of purest light

that radiates no colour nor projects

a shadow, seeming

by degrees

luminous

and transparent,

then radiant and fiery,

manifesting to itself its

mirrored face, dazzling bright

in its own essence,

observed by

itself,

to itself only known

the conditioned fullness

of the unconditioned abeyance,

the circle locked with the square,

the curve straining against the tangent.

III

One timeless momentum

the bow arched, the string quivered;

being by compulsion caught

and volition seized,

at once

is released

a speeding shaft of thought,

through seven permutations whirling,

thrilling the passive womb

at the point of impact,

irradiating around it

instantaneously,

an immaculate

field of unity,

between the centre and

the circumference vibrating,

from the zenith to the nadir gyrrating.

IV

In the third heavenly

circuit, the primordial point

generated a continuous horizontal line;

crossed vertically from

within without,

at the

intersection of

possibility and necessity,

there crystallised in the firmament

a glittering star of glory

wrought and beauty spun,

unbegotten born,

non-existent known,

directionlike converging

and dispersing effulgent beams

of nine and forty prismatic rays,

which hang from it by the finest threads.

~~~~~~~~

An Introduction to Mazhar

From a stylistic point of view, the poem may be regarded as an experiment in symbolic poetry. A symbol is an image or an idea with multiple levels of significance. The language of symbolism is an essential feature of Ismaili literature, where the principles of tanzil (literal interpretation) and tawil (allegorical interpretation) correspond to the zahir (exoteric) and batin (esoteric) dimensions of meaning respectively. This poem too employs a variety of symbols, ranging from the purely poetic to the geometrical and mathematical, which may be interpreted upon several planes of exoteric and esoteric significance. No single perspective, however, can possibly exhaust the totality of explicit and implicit meaning of the poem.

The title of the poem, Mazhar, which embodies the fundamental idea of the poem, may be translated into English as Epiphany or more accurately as Theophany, that is to say a manifestation of God. The poem describes such a theophanic process in the form of a symbolic cosmology or creation of the universe. This cosmic transformation, which is basically cyclic in execution, is effected through a series of trinary and septenary emanations without upsetting the primordial Unity of Being. It is by means of the dialectical tension generated between the symbols one, three and seven that the poem attempts to capture the sense of dynamic motion inherent in the Cosmogenesis.

It is impossible in this introductory note to explore the multiple levels of symbolic complexity to be discovered in the poem. It may be possible, however, to delineate the conceptual framework within which the poem may be appreciated or criticised. This framework is basically that formulated by Ismaili philosophers such as Abu Hatim ar-Razi, Abu Ya’qub al-Sijistani and Harnid’ud-din al-Kirmani centuries ago, though not entirely conforming to their cosmological schemes, for a certain degree of poetic license has been used to adapt them to the poet’s purpose. Moreover, a number of original symbols employed here have no counterparts in traditional Ismaili cosmological literature.

Part I of the poem conceives of the Absolute in its original, indivisible, undifferentiated and transcendent state of Unity, which is unknowable, ineffable, above all qualities and attributes. The Absolute has not yet initiated the Dawr al-Saar (Cycle of Epiphany), but remains concealed in the Dawr al-Kashf (Cycle of Occultation). It is in Part II that the first plane of differentiation is effected with the primordial divine epiphany, the Aql-i-Kull (First Intellect), which is the cosmic rational principle. Unlike the Absolute, the Intellect can be predicated with primary attributes and a potentiality for action. It is the mirror in which the Absolute can behold its own qualities of oneness, knowledge, perfection, etc.

The Intellect is not to be regarded as inbi-‘ath (act of emanation). The identity of the Absolute and the Intellect is aptly summarised in the negative and affirmative poles of the declaration: La Ilaha illa’l-Lah. The theophanic process becomes dynamic in Part III with the imperative Amr (Word) of God: Kun (Be! ). The word is the Logos, the first creative principle, the kinetic agent of the Intellect. Its epiphanic field of activity is the passive Nafs-i-Kull (Universal Soul). Their relationship is symbolically expressed in Ismaili literature by the Quranic designations Qalam (Pen) for the Intellect and Lawh (Tablet) for the Soul. The Intellect is the Sabiq (Precursor) and the Soul its Tali (Successor).

Part IV of the poem completes the theophanic cycle in so far as the meta-cosmic plane of reality is concerned. It is in this phase that the celestial archetype of the universe and mankind is manifested which, in Ismaili terminology, bears the name of Adam Ruhani (Spiritual Adam). Though ranking third in the hierarchy of divine epiphanies, he occupies a unique position in the theophanic order, combining within himself the virtues of the Intellect and the Soul that preceded him, as well as the entire spectrum of hierocosmic epiphanies that is to follow him, corresponding to every plane of existence and order of being in the spiritual and material worlds.

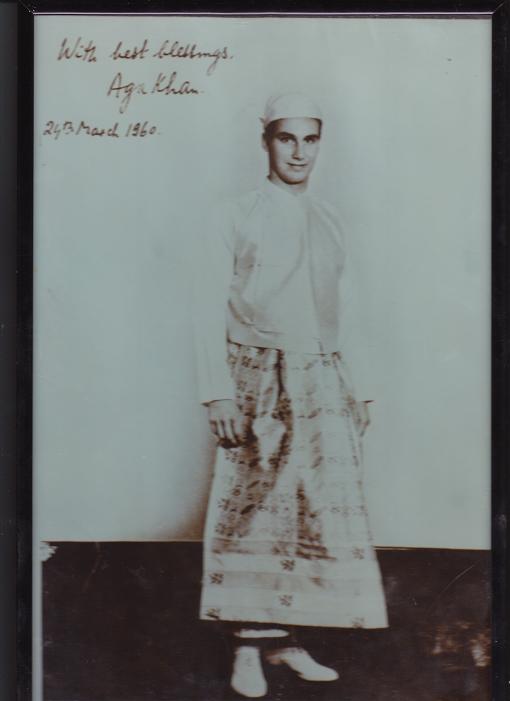

Now the Spiritual Adam is to be identified with the divine Nur (Light) of Imamat, which is symbolised in the poem by the ‘glittering star of glory wrought and beauty spun’. And therefore, the Mazhar par-excellence is the Imam who bears this Light in the terrestrial world. He is the most perfect expression of the divine hypostasis because in him the theomorphosis is fully realised and the Absolute becomes manifest to mortal eyes. It then becomes clear in what manner the Imam represents the macrocosms as al-Isan al-Kabir The Great Man), the microcosmos as al-Insan al-Kamil (The Perfect Man), as well as the Qutb (axis) of the universe, without whom the world would not survive even for an instant.

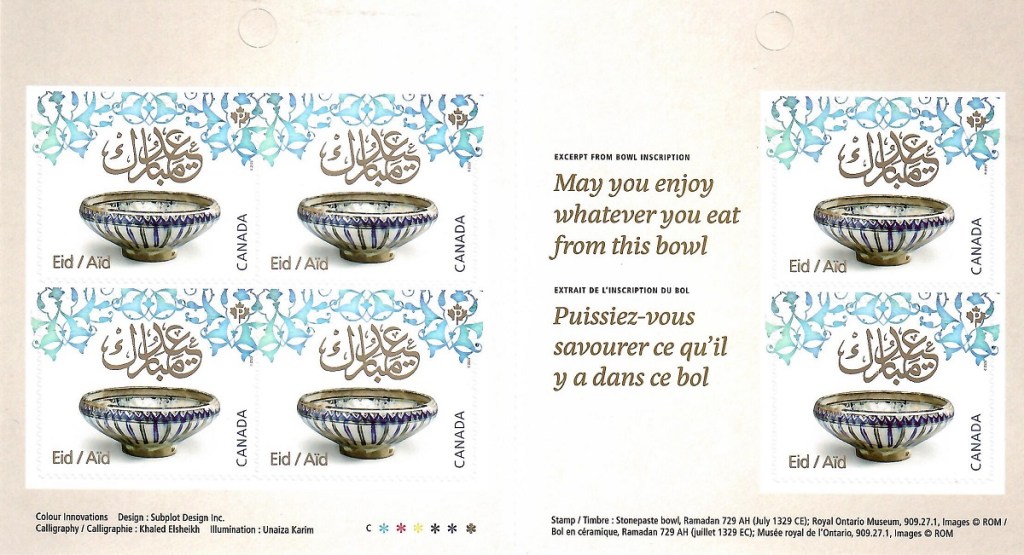

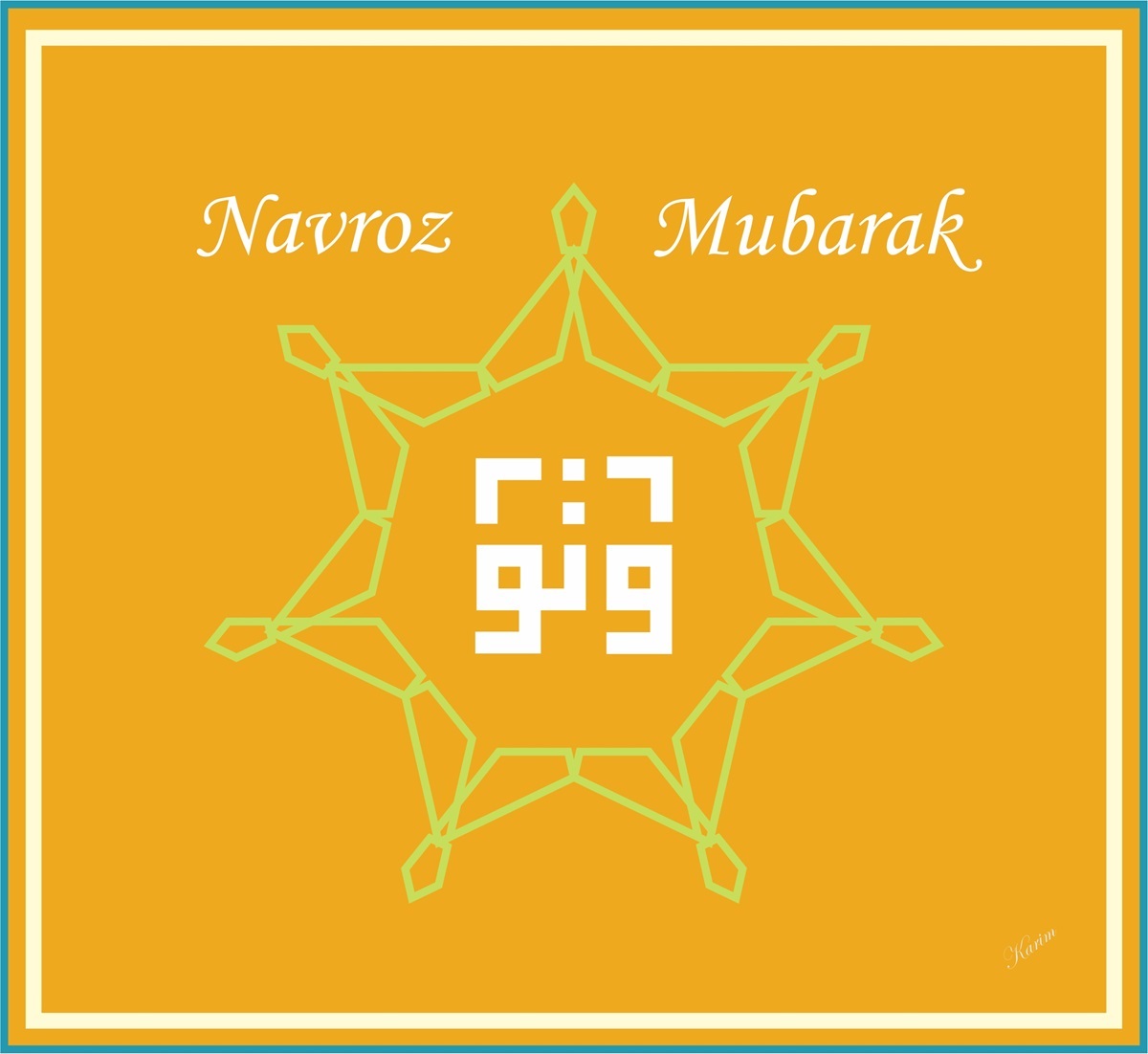

Although the phases of creation, as narrated in the poem, are basically confined to the world of primal spiritual realities, by implication the theophanic process incorporates in one spontaneous sweep the material world also, right down to the contemporary historical period. This is specified in the conclusion of the poem by reference to the ‘nine and forty prismatic rays’, which identifies the Imam of the Age, Mawlana Shah Karim al-Hussaini, His Highness the Aga Khan, the forty-ninth direct descendant of Prophet Muhammad, the spiritual guide and leader of Ismailis, as the master hierophant of the divine mystery and the Mazhar of our times.

Date posted: July 8, 2024.

________________

The poem Mazhar and its introduction have been adapted from Kutub Kassam’s original piece, which appeared in Ilm magazine, Imamat Day Issue (July 1977, pages 38-41), published by His Highness the Aga Khan Shia Imami Ismailia Association for the UK (now known as the Ismaili Tariqah and Religious Education Board or ITREB). Kutub Kassam passed away in 2019 after 40 years of dedicated service to Ismaili Institutions in Africa and the UK as a curriculum developer, editor, writer and researcher. Simerg paid a respectful tribute to Kutub Kassam and his enduring legacy in a special piece published on March 25, 2019.