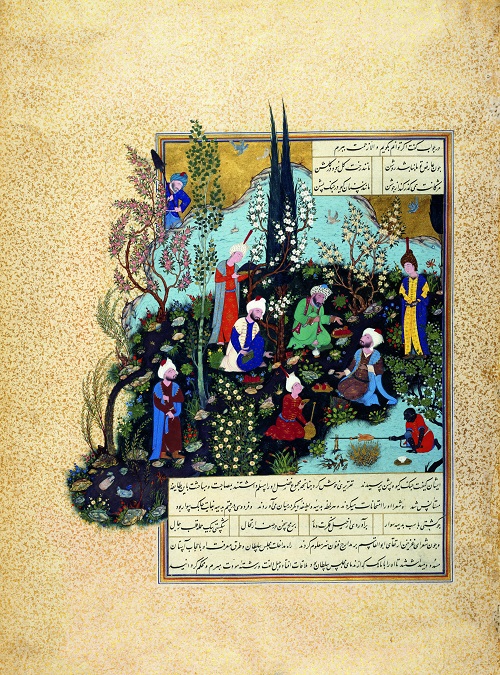

On the occasion of Prince Rahim Aga Khan’s 44th birthday on Monday, October 12, 2015, we are pleased to produce excerpts from his commencement address that he delivered at the Graduation Ceremony of the Institute of the Ismaili Studies held in London, England, in September 2007.

Prince Rahim Aga Khan and Princess Salwa on their wedding day on August 31, 2013. They have one child, son Prince Irfan, who was born on April 11, 2015. Photo Credit: TheIsmaili /Gary Otte. Copyright.

Prince Rahim is the eldest son of the 49th hereditary Ismaili Imam, His Highness Prince Karim Aga Khan, the direct descendant of the Prophet Muhammad (peace be upon him), and Begum Salimah Aga Khan. Prince Rahim graduated from Phillips Academy in Andover, Massachusetts, in 1990, and from Brown University in the United States in 1995. Based at the Secretariat of His Highness at Aiglemont, north of Paris, France, Prince Rahim is an executive Director of the Aga Khan Fund for Economic Development — the economic development arm of the Aga Khan Development Network.

~~~~~

Islam Enjoins Us To Make a Positive and Visible Impact on the World

“…Absolutist, exclusivist, and rejectionist claims to the truth, especially to religious truth, are increasingly heard from all quarters. Rather than seeing religion as a humble process of growth in faith, some people presume to claim that they have arrived at the end of that journey and can therefore speak with near-divine authority…”

Prince Rahim Aga Khan delivering his commencement address at the Graduation Ceremony of the Institute of Ismaili Studies held in London in 2007 at the Ismaili Centre.

BY PRINCE RAHIM AGA KHAN

I am thrilled to join the graduation ceremony in honour of those completing the IIS [Institute of Ismaili Studies] Graduate Programme in Islamic Studies and Humanities. To you, to your families and to all those who have helped you in this achievement, I say mash’Allah.

I am convinced that the institutions of the Imamat and of the Jamat could benefit directly from the contribution of each of you, either in a professional or a voluntary capacity. Such a contribution would certainly be in keeping with the ethic of our faith that makes it incumbent upon each of us to use our blessings –- be they material or intellectual –- to assist our families, to serve the Jamat and the Ummah, and to help improve society, and indeed, all of humanity. The Jamat and its institutions need young and dynamic women and men like you, who are able to draw on the rich heritage of our past, and on the best educations of the present, to address the challenges of the future.

Education, international studies and diplomacy, non-profit leadership, media, development, law, and regional studies will all be among the most relevant fields of expertise in the decades ahead. This will be particularly true in the developing world.

I was impressed to learn that amongst you are represented five different nationalities, as are several diverse cultural traditions of our Jamat. I am certain that this diversity has enhanced your classroom experience, and I am confident that it will have given you a deeper appreciation of the meaning and value of diversity itself.

We are all aware that we live in a world where diversity is often evoked as a threat and, more particularly, where diversity in the interpretation of a faith can be seen as a sign of disloyalty. This phenomenon is sometimes perceived to apply principally to Muslims, but it also exists in other societies. Absolutist, exclusivist, and rejectionist claims to the truth, especially to religious truth, are increasingly heard from all quarters. Rather than seeing religion as a humble process of growth in faith, some people presume to claim that they have arrived at the end of that journey and can therefore speak with near-divine authority.

Unfortunately, in some parts of the Muslim world today, hostility to diverse interpretations of Islam, and lack of religious tolerance, have become chronic, and worsening, problems. Sometimes these attitudes have led to hatred and violence. At the root of the problem is an artificial notion amongst some Muslims, and other people, that there is, or could ever be, a restricted, monolithic reality called Islam.

Our Ismaili tradition, however, has always accepted the spirit of pluralism among schools of interpretation of the faith, and seen this not as a negative value, but as a true reflection of divine plenitude. Indeed, pluralism is seen as essential to the very survival of humanity. Through your studies you have known the many Qur’anic verses and hadiths of our beloved Prophet Muhammad (peace be upon him) that acknowledge and extol the value of diversity within human societies. You all know, I am sure, the hadith to the effect that differences of interpretation between Muslim traditions should be seen as a sign of the mercy of Allah.

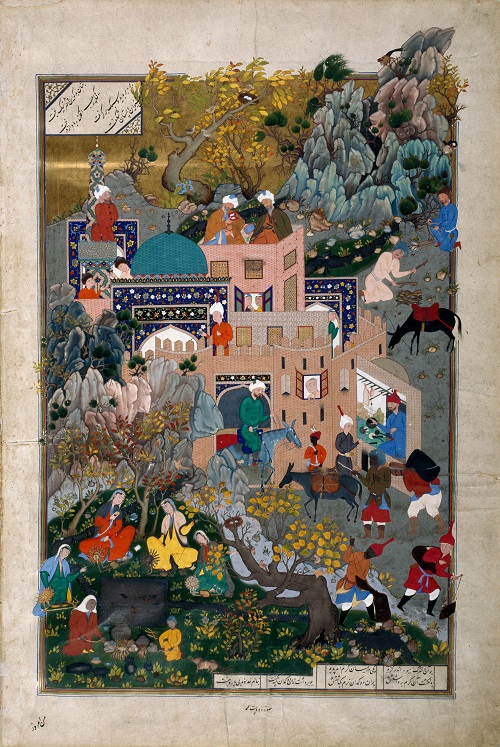

It should also be clear to anyone who has studied Islamic history or literature, that Islam is, and has always been, a quest that has taken many forms. It has manifested itself in many ways — in different times, amongst different peoples, with changing and evolving emphases, responding to changing human needs, preoccupations, and aspirations.

Even during the early centuries of Islam, there was diversity of intellectual approaches among Muslims. Today, however — both outside the Islamic world and inside it — many people have lost sight of, or wish to be blind to, Islam’s diversity, and to its historical evolution in time and place along a multitude of paths. It befalls us, then, to help those outside the Muslim World to understand Islamic diversity, even as we provide an intellectual counterpoint to those within Islam who would reject it.

I hope that you, as graduates of this programme, will include this message in your own ways in the years ahead, through your work and your words, by your attitudes, by your actions, and by example.

The untrue and unfair, but increasingly widespread equating of the words “Islam” and “Muslim” with “intolerance”, sometimes even with the word “terrorism”, could lead some Muslims to feel despair, indignation, or even shame. To me, however, the current global focus on the Muslim world, and on Islam itself, presents a golden opportunity for us to educate and enlighten, while actively exemplifying the counterpoint I mentioned before. To my eyes, it creates an opportunity, and an even-greater obligation for us to make a positive and visible impact on the world – on culture and art, science and philosophy, politics and ecology, among others.

In order to respond to this opportunity, it will be crucial to reverse another damaging consequence of intolerance, which has been the dissuasion of many Muslim populations from seeking access to what has been called the Knowledge Society. Without an acceptance of diversity, without the ability to harness the creativity that stems from pluralism, the very spirit of the Knowledge Society is stifled. We must encourage, I believe, that Muslims of all communities come together, working collaboratively to tap into the vast endowment of knowledge available today, and without which progress is, if not halted, at least deferred. This cannot be done in the absence of open-mindedness and tolerance.

Implicit in this approach is the need for humility, which is also a central Muslim value. We must all search for the answers to the challenges of our generation, within the ethical framework of our faith, and without pre-judging one another or arbitrarily limiting the scope of that search. Like the great Muslim artists, philosophers and scientists of centuries past, we must enthusiastically pursue knowledge on every hand, always ready to embrace a better understanding of Allah’s creation, and always ready to harness this knowledge in improving the quality of life of all peoples.

As you look towards the future, I hope that you will remember that intellectual pursuits should, wherever possible, seek to address the universal aspirations of humankind, both spiritual and concrete. Those aspirations, for our generation more than for any before, are intertwined in a single global community.

It can be overwhelming at times to ponder the vast array of new problems which seem to multiply in this globalised world.

These include the implications of new technologies and new scientific insights, raising new ethical and legal questions. They include delicate and complex ecological issues, such as the great challenge of climate change. They include matters ranging from the widening gap between rich and poor, to issues of proper governance and effective, fair, and representative government, and to the spread of rampant consumerism and greed, at the expense of others, or of our environment. In some communities, illiteracy and innumeracy are not only continuing problems but are even growing problems. And our challenges also include the increasing difficulty of nurturing pluralism in the face of strong normative trends – finding ways to accommodate our differences – even as hugely differing peoples find themselves in much closer contact with one another.

You have been engaged in studies, some of which analysed the achievements of past Muslim civilisations. What I hope you have come to see is that understanding past Muslim achievements, traditions, values, and ethics should also have equipped you exceptionally well to address the great emerging issues of our own times.

As you now graduate into this challenging world, you will be taking with you the hopes of those who founded, and of those who now drive this study programme. Their central hope is that you will become global leaders in a variety of fields, bearing with you as you go, and applying always, the open-mindedness of our tradition, and the ethics of our faith.

Date posted: Monday, October 12, 2015.

__________

We welcome feedback/letters from our readers. Please click Leave a comment.